The Missing Kingdom: Why Fungi Must Be Central to Conservation Strategy

28 December 2025

Published online 17 February 2010

The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) puts the water poverty line at 1,000 m3 per capita annually. However, 13 Middle Eastern countries fall below that line. In Jordan, the water available per person has dropped to 135 m3 annually. In some parts of Yemen, citizens receive drinking water one day per week.

A booming population growth rate in the region is reducing the per capita annual water availability even further, sounding warning bells that something urgently needs to be done.

That is why the International Centre for Agriculture Research in Dry Areas (ICARDA) launched the Water Livelihood Initiative (WLI) last year, to reduce the amount of water used in agriculture in the Middle East.

"This initiative is designed for Middle Eastern countries as a response to the deteriorating livelihoods of the rural communities because of droughts and water scarcity, especially now with climate change and all," said Theib Oweis, who is a researcher with ICARDA. "Of course add to that the biophysical threats such as security and politics. So the region really needs some help."

In most parts of the Middle East, primitive agricultural techniques and technologies mean that a lot of water goes to waste. "We would like to use this initiative to start addressing how we can improve the livelihood of the farmers by using water more effectively and constructively," Oweis added.

The first stage of the project was to set up several workshops to raise awareness of the initiative in rural communities. This was done with a main focus on Egypt and Jordan, as representative samples of the communities that the programme is targeting. The next phase is translating the results of these workshops into proposals for reducing water usage while increasing yield. So, instead of 1 m3 of water producing one unit of yield, it should produce two or even three units.

The programme spans seven countries: Egypt, Jordan, Syria, Lebanon, Palestine, Iraq and Yemen. It is funded by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), with an initial investment of US$1 million to cover the first stage of the project. "After that we expect US$50 to US$60 million," Oweis explained. "What we are developing right now is proposals for countries where USAID missions in the countries themselves can submit money as well."

"This is actually one of the major challenges we are trying to resolve now. But when it comes to working, we are hoping we will get much more substantial money."

There are three main agrosystems involved. The first is rain-fed agriculture, which is present mainly in Jordan and northern Iraq.

The second is irrigated agriculture, which is the most widespread in the region. This is mainly found in Egypt and southern Iraq. "The amount of water is limited, so the only option is to increase the yield from the same amount of water," explained Oweis. "The water is being used inefficiently. We have research that says you can double the yield with the same amount of water currently used."

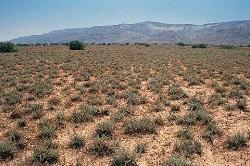

The third is rangelands, which are called 'al-badia' in the region. These are areas of native vegetation that cover large parts of Syria, Jordan and Lebanon. They are mainly fed through underground water. However, overexploitation is leading to the drying up of large areas, which become semi-arid land. "This is a particularly important system because it raises a lot of desertification problems due to over-grazing there. This then starts creeping to irrigated and rain-fed areas to negatively affect them," added Oweis.

Scott Christiansen, who is a senior agricultural development advisor at USAID, explained that the agency funded agriculture programmes extensively in the early 1990s. This funding decreased in the following years in favour of other projects. "But when food and fuel prices shot up in 2007, this refocused many development agencies and donors on agriculture and food security."

ICARDA opted for a bottom-up approach when laying out the details of the project. Instead of going for policy makers in the beginning, they set up focus groups in the different communities to understand what their needs were, and to gauge what techniques would work in each particular place.

"We will go from involving local communities — and involving as many stakeholders as possible — to suggesting policy recommendations for policy makers," said Fadi Karam, who is project manager for the WLI at ICARDA.

Five key US universities will be involved in the project on the technical side. Each of them brings a certain expertise. For example, Texas A&M University brings experience in range management and livestock production, whereas the University of Florida is strong in gender research. They will also be involved in capacity-building programmes for the farmers through ICARDA. There will be both degree and non-degree level training offered to the farmers.

"The American universities are not as strong in working with these communities as us. They don't know them very well, but they know the [science] advancements," said Oweis.

"We come to a problem and we try to solve it. We use what is available on the market and universities to develop solutions. The technical solutions are usually not difficult. It is the integration of these solutions that is hard," he added.

The US universities will also work with regional American universities, such as the American University in Beirut (AUB) and the American University in Cairo (AUC), to deliver the technologies to national universities. This is part of the national portion of the project.

Using these technologies and the data gathered, each country will put together a national plan to implement according to its own set of needs, challenges and community expectations.

Geographical information systems (GIS) are being used in some places to determine the best spots for agriculture and water collection. The technology is basically an evolution of the ancient science of cartography, in which satellites gather and analyse images and data using a computer.

"The big power here is the overlaying capabilities, which means you can bring together spatial data in many forms and combine them and do different types of analyses with them," explained Eddy De Paauw, who is head of the GIS unit in ICARDA.

"We are using [this technology] to identify areas with potential for water harvesting, areas that are suitable for supplemental irrigation to save water, etc. We have developed that in Syria and are now applying it in Libya and probably later in Eretria," he added.

"This is a phased approach," he explained. The first step is identification of good spots. This is done by measuring the amount of moisture in the soil using satellite imagery. "After that, these results are used for more detailed studies. This is what is happening in Syria and Libya right at the moment."

The second phase of the WLI programme began in February 2010, with workshops organized by ICARDA to help national delegations from each of the seven countries put together their action plans. Applications should start directly addressing farmers in the poor rural areas throughout 2010.

doi:10.1038/nmiddleeast.2010.111

Stay connected: