Using AI to control energy for indoor agriculture

30 September 2024

Published online 9 June 2010

The need to bridge the gap between science and public policy in the Arab region is obvious; the environmental and climate policy is no exception. In a region with a long history of autocratic political systems and underfunding of research and development (R&D), the scientific community is lacking both the independence and the resources it needs to drive the public-policy process.

The role of science in the policy cycle cannot be understated. The relationship between science and environmental policy can be categorized in two ways: science-led policy and policy-led science.

Science-led policies, which are the focus here, are those that are needed to respond to environmental issues. For example, in the 1980s, the international community was able to respond to the alarming signals from the scientific community that the ozone layer in the atmosphere is thinning due to a group of chemical compounds called ozone depleting substances (ODS). This led to the creation of a complete set of regulatory, scientific and financial measures to address the problem.

After decades of implementing those measures, scientific evidence that the stratospheric ozone layer is recovering — although it still needs many years to heal completely — has become increasingly available.

Generally speaking, science can help define the environmental problem, monitor its development, size-up its socioeconomic effects and, most importantly, provide alternative solutions to the problem. In addition, science can help evaluate the effectiveness of the policy measures implemented.

Unfortunately, policy makers often fail to consider the scientific signals for political, economic or other reasons. In many cases, they use scientific uncertainties as an excuse for inaction. However, the reality of life has been, and will continue to be, that science will never be complete. This is why the international community had agreed to adopt the 'precautionary' principle. It simply restates the old saying that "prevention is better than cure". This principle, adopted in the Rio Declaration on Environment and Development in 1992, has become one of the major ethics widely considered in international environmental diplomacy.

In that same year, and in response to many alarming signals from the scientific community, >190 countries signed the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). Article 2 of the convention set its ultimate objective as stabilizing atmospheric greenhouse gas (GHG) concentrations "at a level that would prevent dangerous anthropogenic interference with the climate system. Such a level [of GHG concentrations] should be achieved within a time-frame sufficient to allow ecosystems to adapt naturally to climate change, to ensure that food production is not threatened and to enable economic development to proceed in a sustainable manner."

Since 1992, parties to the convention have failed to quantify the concentration of GHGs that would be considered dangerous. The underlying reasons for this failure are many. The climate-change challenge has moved from being an environmental problem to being a complicated development issue, topping the political agenda of the world's leaders. A global mean temperature increase of >2 °C is expected to result in costly adaptation measures, considerable effects that exceed the adaptive capacity of many systems and a greatly increased risk of large-scale irreversible effects.

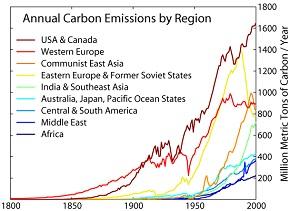

Issues of responsibility also haunt the discussions. Although 20 countries are producing >80% of the total global GHG emissions, it is the rest of the world's population that will suffer most of the projected climate-change effects. They will also disproportionately affect the poorest communities, offering far-reaching challenges to achieving sustainable development. This dilemma has been a major obstacle that world negotiators are striving to overcome during the negotiation process.

If the Arab countries have failed, for decades, to join hand on most fronts, the climate change problem might be a 'golden opportunity' to start.

By the end of this century, the Arab region is projected to become considerably hotter and drier. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Fourth Assessment Report estimates an increase in temperature to 2 °C by mid-century and to >4 °C by 2100. IPCC models also predict that the Arab region will suffer greater precipitation losses compared with other regions, with water run-off projected to drop by 20–30% by mid-century. The combined effect of higher temperatures and reduced precipitation will increase the frequency and severity of extreme weather events.

In North Africa particularly, droughts will become more frequent and intense, continuing recent trends. What used to be one severe event per decade at the beginning of the century has increased to five or six. In addition, as major parts of the Arab region's economic activity and population centres are located in the coastal zones, sea-level rise is a major risk. A recent simulation carried out by Boston University's Center for Remote Sensing in the United States revealed that a sea-level rise of only 1 m would have a direct impact on ~41,500 km2 of the Arab coast. The most serious effects of sea-level rise would be in Egypt, Tunisia, Morocco, Algeria, Kuwait, Qatar, Bahrain and the United Arab Emirates (UAE).

The recently published Arab Human Development Report 2009: Challenges to Human Security in the Arab Countries identifies the pressure on environmental resources as one of the main factors for achieving human security in the region. The Arab region is among those least responsible for emissions of GHGs. According to the global Human Development Report 2007/2008 and the World Development Indicators 2007, the region's share of carbon dioxide emissions was no more than 4.7% — lower than all other regions except sub-Saharan Africa. However, the region is also among those most in danger of becoming a severe victim of climate change.

The national socioeconomic circumstances of the Arab countries show considerable variation according to the human development index (HDI) rankings. Libya and the Gulf region, with the exception of the populous Saudi Arabia, are characterized by a relatively small population and a huge endowment of hydrocarbons. They have a significantly higher HDI ranking than other Arab countries. Kuwait is the Arab country with the highest global HDI ranking, whereas Yemen has the lowest. Six Arab countries — Comoros, Djibouti, Mauritania, Sudan, Somalia and Yemen — are included on the world's 50 least developing countries (LDC) list.

The prospects of the Arab region as a whole for poverty eradication are encouraging. However, wide gaps within the Arab subregions remain. Iraq, Palestine and the Arab LDCs will probably fail to meet the poverty-related targets of the Millennium Development Goals (MDG) by 2015 without drastic improvements in their economic and political situation. Climate change would clearly add an extra burden on those countries in fulfilling their targets.

This wide gap between different Arab countries in terms of levels of human development made it difficult to formulate a harmonized Arab climate policy. However, the Council of Arab Ministers Responsible for Environment (CAMRE) of the League of Arab States adopted, in 2007, a political declaration that outlines the main elements of an Arab position in the climate negotiations.

The declaration recognized that the Arab region, located within a dry and arid region, will be one of the most vulnerable areas to the potential effects of climate change. These include a higher threat to coastal zones, increased intensity of drought and desertification, scarcity of water resources, and the spread of epidemics and diseases. It emphasizes the need to render mainstream climate change in the development policies, strategies and programmes of the Arab countries. However, it also calls for consideration of the interests of Arab oil-producing countries, the economies of which could be affected by international efforts to mitigate climate change.

Remarkably, the same document identifies the major priority areas for mitigation and adaptation to climate change. It stresses that governments play the major role in addressing the climate-change challenge, but in coordination with all parties concerned, including the scientific community.

Robert A. Rohde / Global Warming Art

The current weak capacity of science and technology in the Arab region can be attributed to several main factors. One is an overall lack of interest in science by governments. They devote minimal funds to education and science, compared with those set aside for other issues, such as military expenditures. Another crucial factor is the deteriorating education systems. These factors, along with the inadequate infrastructure and support systems, create an environment that is not conducive to R&D.

On a global level, the scientific literature originating in the Arab world does not exceed 1.1% of the world production. In terms of the ratio between gross domestic expenditure on R&D (GERD) and gross domestic product (GDP) investment, Egypt, Jordan, Kuwait and Saudi Arabia spend the most, devoting 0.2% of GDP to GERD. The figure for the remainder of the Arab region is at times <0.1%. Expenditure on R&D by Arab countries is at best one-tenth of that spent in industrialized countries. According to United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) statistics, some countries, such as Israel, spend >4% of GDP on R&D.

This enormous underfunding of R&D cannot be expected to produce tangible results. So it is not surprising that policy development in most of the Arab countries does not consider scientific evidence as a major factor in the policy-making process. Arab policy makers do not believe in scientific research and studies, which are looked at as a luxury that cannot be afforded.

Research targeting different aspects of climate change is no exception. So far, only a few Arab research institutions can claim that they are working in these fields. With few exceptions, these projects are mostly in early stages. In the study areas of vulnerability and adaptation of the Arab region, non-Arabs produce most of the literature on which the IPCC authoritative reports are based. The number of Arab scientists contributing to the IPCC reports is relatively small.

Adaptation to the adverse effects of climate change is a priority for the Arab region, at least according to the Arab ministerial declaration, but the body of literature available on these topics does not reflect that.

In spite of the rhetoric from Arab politicians, and several formal documents, declarations and strategies produced by the League of Arab States, the Arab–Arab cooperation in these fields has not materialized. The climate-change challenge is so daunting that no single country, whatever its resources, can face it alone. With weak R&D capacity at the national levels, Arab countries have no other alternative but to cooperate. If the Arab countries have failed, for decades, to join hand on most fronts, the climate change problem might be a 'golden opportunity' to start.

This will not be realized without strong political will, public pressure and raising the voices of scientists. Practically speaking, we should immediately start with public education. The level of awareness of climate change and its future implications on the Arab citizen's daily life is improving, but it still has a long way to go. Civil society organizations and the media should play the leading role in this long-term iterative process.

Arab scientists, regardless of their weak influencing power, should strive to make their voices heard. Climate change is an issue that reaches out to all aspects of our lives. Research is badly needed in the areas of agriculture, water resources, marine resources, public health, biotechnology and renewable energy, to name just a few.

We need to mobilize the fragmented research assets across the Arab region to implement a regional research strategy to determine, as accurately as possible, the future effects of climate change.

It is sad that the science community continues to debate whether the Nile Delta in Egypt will be influenced by sea-level rise, citing weak research and sources. In the ongoing absence of solid science-based evidence, the public and policy makers will continue to receive mixed messages, leading, at best, to inaction.

Ibrahim Abdel Gelil is the vice dean of technological studies and director of the Environmental Management Programme in the College of Graduate Studies, Arabian Gulf University, Bahrain.

doi:10.1038/nmiddleeast.2010.160

Stay connected: