Using AI to control energy for indoor agriculture

30 September 2024

Published online 10 July 2010

A new World Bank report on HIV/AIDS in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) released last week calls for further scientific research into the epidemic to inform policy-makers, and to shift the focus of public health programmes to people especially at risk.

The report "Characterizing the HIV/AIDS Epidemic in the Middle East and North Africa: Time for Strategic Action" is the most comprehensive scientific study on the HIV epidemic in the region to date.

The perceived links between the disease and promiscuous sex and drug abuse, behaviours unacceptable to societies in the region and which are prosecuted in many MENA countries, may have led to HIV/AIDS being neglected. As a result, research into the spread and prevention of HIV in the region lags behind the rest of the world.

"There was also a perception that data are hidden from the public. These misconceptions, however, reflect poor understanding of the nature of this region," said Laith Abu-Raddad, the lead author of the study, and assistant professor of public health at the Infectious Disease Epidemiology Group in Weill Cornell Medical College in Qatar.

The lack of HIV data in MENA is partly caused by prejudice and stigma. "It is true that sometimes certain governments will try to hide results. Many people with HIV would not announce their status, and many others are diagnosed overseas and no one here would know," said Abdelhady Mesbah, a microbiology and immunology consultant in Egypt. "But this is slowly changing. Now people are coming forward and we are convincing them to go to official sources."

The research, funded by the World Bank, the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS), was released last week on the sidelines of a conference on HIV/AIDS policy dialogue in Dubai, United Arab Emirates.

The report criticises the dearth in scientific research into HIV and other sexually transmitted diseases in the region. What little work that is taking place is scattered among different institutions, rather than coordinated in a unified effort.

"Extensive HIV quality research is still in its infancy. Most of the research is not being done in academia even though this is the natural carrier of scientific research. This affected the output of the research and the dissemination avenues for the findings," added Abu-Raddad.

Opportunities for formulating science-based policies to counter the epidemic are being missed. For instance, collecting additional basic demographic and behavioural data for the millions of HIV tests conducted annually can provide some insight about the populations where HIV incidence is increasing. Conducting some additional serological tests would also significantly improve the analyses of the epidemic in the region.

"Convincing policy-makers is harder but this is part of the bigger problem in this region of policy not being driven by an evidence-based approach," said Abu-Raddad.

"However there are encouraging signs," he added. Iran and Morocco have shown their willingness to confront the disease. Other countries, such as Qatar, have begun putting in place a public health system based on scientific research.

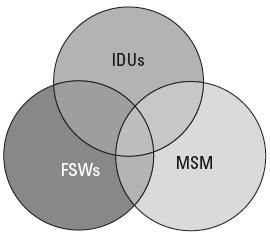

Waiting until the epidemic spreads further, however, might not be the wisest decision. The evidence reveals that there is, as yet, no widespread epidemic in the region, but certain sub-populations, including men who have sex with men and injecting drug users (IDUs), are more at risk of HIV infection. Taking preventative steps now could stop the virus establishing itself within these groups, but the window of opportunity will eventually shut if nothing is done.

The report found the highest HIV prevalence in IDUs, reaching up to 15% of those in Iran. However, since the population of IDUs is small, this was not the most common mode of transmission. "Heterosexual sex is the leading mode of transmission and most HIV infections are likely linked acquisitions among commercial sex networks," said Abu-Raddad.

The different areas of MENA are susceptible to different modes of transmission. "In Iran, the highest risk is in IDUs, but in Sudan, for example, it is through heterosexual intercourse," explained Mesbah. "In Egypt you would find a mixture of all types of risk groups, whether in IDUs, commercial sex workers or in the homosexual community."

The researchers found that high-risk groups in some of the countries studied had a relatively low HIV prevalence, compared with other regions of the world. HIV incidence remains at low levels for years in these groups despite the risks. "We cannot understand this well but we think this is either because of lack of virus introduction into these groups or the nature of social, sexual and injecting networks among them," explained Abu-Raddad.

Abu-Raddad stressed that the main problem is that HIV/AIDS policy was directed at the general population, which is wasting resources and yielding minimal results. A more focused response to those risk groups identified in the report would help the region effectively respond to HIV.

This is easier said than done; due to the socio-cultural and religious character of the MENA region, many of those most at risk, especially the homosexual community, live on the margins of society. Measures that might work elsewhere, like safe-sex campaigns or legalisation of commercial sex, would fall short owing to local resistance.

"There is a difference between accepting homosexuality in society and accepting to treat homosexuals," added Mesbah. "No one should be denied the right to treatment, whether I agree with them or not."

"This leads to a mismatch in communication and to making HIV policy dialogue between some international organizations and other advocacy groups and country-level public health officials as a dialogue between deaf people," said Abu-Raddad. "In the process little gets done."

Abu-Raddad suggests that the best solution is to disentangle the HIV/AIDS issue from the political discourse. Rather than using it to push certain agendas, it should be treated as a public health issue. Following this line of thought, Iran began distributing clean syringes in its prisons, once they learnt they were becoming hotbeds for the spread of the virus.

"This is, however, an unpopular approach," Abu-Raddad continued. "Though the Iranian response to the HIV epidemic among IDUs shows that this is a practical approach and can yield results."

lists the HIV transmission modes for some of the countries of the MENA region.

doi:10.1038/nmiddleeast.2010.173

Stay connected: