Using AI to control energy for indoor agriculture

30 September 2024

Published online 9 April 2012

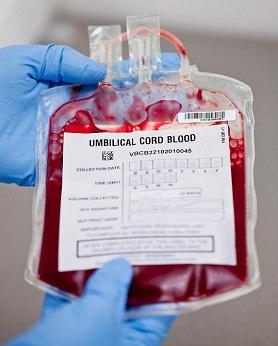

Private stem cell banking is a steadily growing business in the Arab region, with parents increasingly aware of the potentially life-saving benefit of preserving a newborn's umbilical cord. Cord blood treatment is currently used in therapy for a number of cancers; blood, metabolic and immune disorders. While harvesting and storing blood from the umbilical cord is not a controversial medical practice in the Middle East, there are several ethical issues that need to be considered.

Umbilical cord blood transplantation, even from a mismatched donor, is an effective alternative treatment for a bone marrow transplant if marrow from a matched donor is unavailable. Hind Humaidan, director of the Cord Blood Bank set up in 2003 at King Faisal Specialist Hospital and Research Centre in Saudi Arabia, says her hospital has performed more than 3,500 bone marrow transplants, but that finding a suitable donor is often a major obstacle.

Since the cord blood bank's launch, it has collected 3,725 UCB samples. Humaidan says the non-profit public cord bank has benefited patients, and has resulted in huge savings for the hospital. "We used to pay US$30,000 to US$35,000 to import and transplant UCB. The cost to transplant a local unit from our bank is US$7,300."

The American Academy of Paediatrics, Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists and the World Marrow Donor Association have all questioned the benefit of private stem cell banking, arguing there is no real advantage in autologous transplantation. The banks have also been criticized for aggressive marketing to expectant parents. "You cannot tell people if you don't donate your baby's umbilical cord blood cells (UCB), your child may possibly die. That's just wrong," said Rajan Jethwa, head of Virgin Health Bank (VHB) in Qatar, speaking at a panel discussion at the Qatar International Conference on Stem Cell Science and Policy in February 2012

Jethwa argues that the aggressive marketing of some private cell banks is driven by a commercial imperative which can override promoting the medical value of stem-cell preservation. Although VHB, headquartered in the United Kingdom, has existed as a private enterprise since opening in Qatar in 2009, a new public-private model will come into effect this year under which a sample of the child's cells will be banked privately, and the remainder, with parental permission, will be placed into the public bank. "Thus social enterprises can make a profit and do good," Jethwa explains. "I like to think we are the architects of Arab stem cell banks."

The state will pay the bank to operate the public donor bank, which will be fully managed by VHB.

Medical professionals encourage the donation of UCB to public stem cell banks since, like blood banks, they benefit the wider community. Humaidan, suggests banks should accurately explain to parents the terms of donation and how it can benefit others. "Most mothers, if approached correctly, agree to donate cord blood."

"In Saudi Arabia, large families are common, so there's a larger donor pool for UCB," says Humaidan, suggesting this would solve the problem of the lack of matched donors. Since the bank opened in 2003, the hospital has done 219 successful UCB transplants.

Both Humaidan and Jethwa confirm that once parents donate umbilical cords to a public bank by informed consent, they concede control of the tissue. "However, if it's needed for a transplant and it's still available, it will be given to the patient," says Humaidan.

doi:10.1038/nmiddleeast.2012.51

Stay connected: