Using AI to control energy for indoor agriculture

30 September 2024

Published online 10 October 2013

The 'green corridor' hypothesis, which explains early human migration from Africa, has been strengthened by evidence of ancient rivers that flowed north through the Sahara desert some 100,000 years ago.

Geological data suggest that a wetter climate during the period between the last two ice ages produced rainfall on the mountain ranges in the Sahara and created green corridors through which early modern humans migrated from Africa.

The obstacle of the Sahara desert to human dispersal has long raised questions about the migration of Homo sapiens who originated in sub-Saharan Africa. The green corridor theory suggests rivers would have provided fertile habitats for animals and crops allowing humans to migrate north.

Geographers from the University of Hull have produced what they say is the strongest evidence yet for the hypothesis by producing a computer simulation of the palaeoclimate in northern Africa, which models the flow of water across the region.

One of the study's authors, Mike Rogerson, says the key elements of the simulation are satellite-derived topography of northern Africa, an Earth landscape model for modelling surface activity, and rainfall data. "Archaeologists and marine scientists all say that these fossil rivers flowed, but our team is the first to put the physics on the ground and see if it allows them to hit the [Mediterranean] coast."

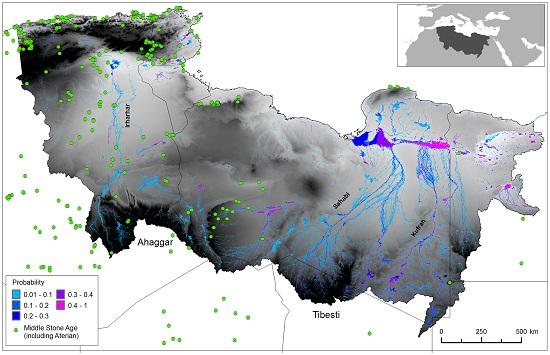

Their results, published in the open access journal PLoS ONE, point to the existence of three river systems, all of which drained northwards from the Ahaggar and Tibesti mountain ranges in central Sahara towards the Mediterranean.

The western-most of these ancient rivers, the Irharhar, would have been located in what is now eastern Algeria. The simulation indicates it flowed directly north, linking the southern mountainous regions with monsoon climates to the temperate Mediterranean climate. It was only active for about three months per year, during the monsoon season.

The Sahabi and Kufrah rivers, located about 2,000Km to the east, flowed perennially, but were shorter and ended in the arid and semi-arid regions of the desert before reaching the Mediterranean.

The researchers say that the Irharhar was the most likely to have provided a viable migration route. The supposed path of the river system is dotted with many archaeological sites dating from the Middle Stone Age. The river systems that lay to the east don't feature such sites, supporting the researchers' theory that the Irharhar river system was the preferred route for migration.

"The model clearly shows that it would have been green enough for human migration out of Africa," says palaeoclimatologist Mark Maslin of University College London. "But there would have been plenty of other opportunities for migration [in the preceding 1.8m years], and the study doesn't address why humans would have migrated at this particular time."

doi:10.1038/nmiddleeast.2013.178

Stay connected: