Using AI to control energy for indoor agriculture

30 September 2024

Published online 22 December 2013

Amid speculation over the basis of religion, some are asking if religious fundamentalism is a sign of a deep disorder, rather than deep faith.

Neuroscientists are entering the debate over the underlying reason for religious fanaticism.

Fundamentalism cannot be strictly defined on a scale of devoutness or by political leanings. And the definition of fanaticism varies. For some, a fundamentalist is a literalist, for others he or she is a terrorist.

Fundamentalism at its worst — that results in violent conflict or aims to impose a world view that compromises other beliefs and human rights – is abhorrent to the great majority of society and scientists are trying to establish the roots of such dangerous mind-sets.

Is adopting this type of fundamentalism a personal choice, or a condition that may one day be seen as curable? Is it an anomaly, a "defect in the brain"?

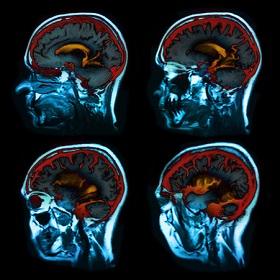

Research shows that a religious experience can alter the brain. A study found that hippocampus atrophy (brain shrinkage) is more acute in people with strong religious affiliations, and those reporting "life-changing religious experiences."

The shrinking of this brain region is usually associated with mental health problems such depression and dementia — and the study suggested it can result when people experience higher levels of stress because of religion. The sources of stress could be anything from guilt at perceived sinfulness, to believing one is persecuted by society for holding particular religious beliefs.

The results may help dispel the belief, previously held by neurologists and many people of faith, that religious experiences are beneficial in absolute terms.

Several neuroscientists agree that fundamentalism, or the choice to embrace a certain path, seems to result from free will as well as being subject to external forces — whether through manipulation (or brainwashing), imposed rituals or a method of upbringing. It has been accepted that the brain affects and is affected by the experience.

For example, studies have shown that believers commonly use a belief in God as their moral compass, but that this compass is dependent on existing beliefs. For example, if someone declares human cloning as a sin, it is likely he or she is not only speaking from knowledge of faith texts, but also projecting his beliefs on God — religious texts notwithstanding.

But there is also a neurological dimension. Everything affects the brain in different ways and each person might be affected differently, says Andrew Newberg, a radiologist at Thomas Jefferson University and Hospital, Philadelphia. Long-term religiosity can alter brain volume or engage different areas of the brain, leading to cortical changes that affect a person's cognitive, mental or emotional state.

There is a delicate balance between free will and neurological processes. Kathleen Taylor, a neuroscientist at Oxford University and author of Brainwashing: The Science of Thought Control, explains: "It's not a clear distinction, especially as brain 'rewiring' can itself occur over multiple timescales and at different levels of permanence."

Taylor says: "The initial choice may be free, but then it leads to a much more pressurized environment" – which could lead to brainwashing.

Who decides whose beliefs are OK and who needs 'treatment'?

Research by the New School for Social Research and University of British Columbia found that religious rituals can influence a person's support for hostility towards other faith groups. In four studies looking at six religions, including Islam and Judaism in the Middle East, researchers led by Jeremy Ginges, a psychologist at the New School for Social Research, New York, found that regular attendance of religious services — mosques or synagogues — sometimes led to a combination of willing martyrdom and out-group hostility, though regular prayer did not.

Regulars at mosques and Israeli settlers who attended formal sermons in a survey showed support for suicide attacks, even describing the acts as heroic — while denying any affiliation with political Islam or organisations that promote hostility toward the other.

The study found that the correlation between religiosity and suicide attacks may come from religion's tendency to enhance group identity and cooperation through collective ritual.

The researchers found that propaganda by religious clerks can have an influence, but is not pivotal. According to Ginges, their theory held "even when we controlled for identification with organisations carrying out suicide attacks" or "statistically controlled for support of political Islam."

Modern science has pondered the nature of fundamentalism for the last few decades. But so far the consensus is not leaning towards strictly classifying fundamentalism as an illness, despite the suggestion by some commentators.

Last June, Taylor was quoted in The Times and The Daily Mail as saying that fundamentalism may be a mental disturbance that can be cured — with Islamic fundamentalism given as an example of such disturbances. However, she contends she was misquoted. Viewing some religious beliefs as treatable as any other mental illness may not be tenable, she says. "Who decides whose beliefs are OK and who needs 'treatment'?

"What most Westerners seem to mean when they talk about fundamentalism is not actually fundamentalism at all, but bigotry," she adds. "If anything needs curing, it's that."

A study of university students and their parents found that religious fundamentalism, exhibited through rigid adherence and intolerance towards different religious views, correlated quite highly with religious ethnocentrism, as well as with —to lesser degrees — hostility toward homosexuals and prejudice against racial-ethnic minorities.

It seems that being religious may not be the problem as much as the negative emotions

It was not the faith per se that was the issue but the fact that doctrine was aggressively drilled into the students at an early age. In the words of the researcher, the fundamentalist students "reported receiving strong training in identifying with the family's religion from an early age. But, by comparison, they reported virtually no stress being placed on their radical identification."

This identification, the study concluded, produced a template of discrimination that led to prejudices.

"If a person feels connected only to a small group or a specific doctrine, they might view others and other beliefs in a much more exclusionary or negative way," says Newberg, who also heads research at Myrna Brind Center of Integrative Medicine, Philadelphia, and author of Why God Won't Go Away: Brain Science and the Biology of Belief.

He adds that whether a religious practice is negative or positive is directed by two factors: sense of connectedness to the idea or religious group, and the emotional paradigm in which this connection is made. "If the emotional tone is negative — i.e. people who don't believe what we believe are evil, we should kill people who believe differently — then the result is negative emotions such as fear and hatred, and outwardly destructive behaviors.

"Given what we know at the moment, it seems that being religious may not be the problem as much as the negative emotions. Thus, it might be more a redirection that might be useful rather than a treatment," he says.

But even if science demonstrates that religious fundamentalism is indeed damaging to the brain, and is a social deviation from the "norm" (after coining universally acceptable definitions for fundamentalism, "treatment" and "norm"), does this mean that, for instance, radical Islam or Christianity, can be classified as a mental illness?

"We use the term 'mental illness' about people who don't seem to function well in our society, or who think differently about important issues than we do, or who act to harm us … but that's because, to us, the way we do things is the only 'right' way," says Taylor.

A mental illness, it is generally agreed, is displayed by dysfunction to the point where daily living becomes hard. So far, we cannot say this is the case for the religious fanatics, says Taylor. "The radical political [or religious] activists we're all afraid of can function well enough to plan sophisticated mass terror attacks."

doi:10.1038/nmiddleeast.2013.245

Stay connected: