Using AI to control energy for indoor agriculture

30 September 2024

Published online 29 May 2013

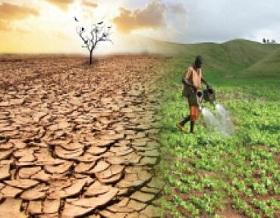

The Dry Systems programme launched last week in Amman aims to help farmers exposed to the effects of climate change.

A 3-year initiative to introduce foreign crop varieties and farming techniques to five vast, dry areas has been set up to help the world's most vulnerable populations survive the damaging effects of climate change on their livelihoods.

The CGIAR Research Program on Dryland Systems brings together significant financial supporters, such as the World Bank, with agricultural research partners from 28 countries and more than 15 CGIAR research centres.

CGIAR's director of the Dry Systems programme, Bill Payne, said that donors encouraged the foundation to coordinate centres to share their expertise in specific geographical areas or particular crops. Although CGIAR has existed since 1971, the research centres under its auspices have mainly operated independently1. They hope that collaboration under the leadership of CGIAR's International Center for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas (ICARDA), will lead to better guidance for farmers in dry areas.

"West Asia, North Africa and some southern parts of Africa as well as the highlands will be the most heavily hit by climate change," says Payne. "Almost all global circulation models concur it will get much hotter and much drier."

Dry areas are home to 2.5 billion people and account for more than 40% of the earth's surface2. Since these populations often have high rates of poverty, they are especially vulnerable to crop failures caused by climate change. Payne says that although the programme cannot mitigate climate change, it might help poor farmers adapt by providing crops that can tolerate higher temperatures and salinity levels. It also installs water systems and facilitates local research.

"It's not to say that a lot of the research by agricultural scientists in CGIAR hasn't had impact before, we just have to be more thoughtful about how we explain it and demonstrate it," says Polly Ericksen of the International Livestock Research Institute, which is overseeing East and Southern Africa in the Dry Systems programme.

West Asia, North Africa and some southern parts of Africa as well as the highlands will be the most heavily hit by climate change.

Salvatore Ceccarelli, a CGIAR consultant who is not affiliated with the Dry Systems project, warned it was important that CGIAR took a clear stance on the GM question to ensure that farmers are not dependent on seed imports, market prices and potentially-damaging herbicides and pesticides, even if that policy could alienate certain funders.

However, Payne says that none of the seeds used in the programme have patents owned by companies, and will be available for purchase by national governments.

Some of the programme's 'action sites' will incorporate new technologies and methods, and also build on existing agriculture techniques used by local farmers. Antoine Kalinganire of the World Agroforestry Centre, which oversees West Africa and Dry Savannah for the programme, suggests, however, that farmers could benefit from the reintroduction of species that have disappeared as well as cultivating current crops and trees.

"Some species, such as medicinal plants, have completely degraded from the landscape," he says. "So you take species from where they are viable and bring them close to the farmers."

Ceccarelli says that as crops are brought into different environments it will be important to empower farmers to cultivate new varieties of seeds themselves. This process, called participatory plant breeding3 is recommended by the World Bank4. He says that through participating, farmers could break the monopoly that a few large, multinational agricultural firms have over R&D in the industry.

doi:10.1038/nmiddleeast.2013.78

Stay connected: