Using AI to control energy for indoor agriculture

30 September 2024

Published online 6 August 2014

The threat of an outbreak of the deadly Ebola virus in the Middle East is very real. The region must improve its preparedness to fight off the disease, and in the worst-case scenario, to respond to it.

The scale of this ongoing outbreak is unprecedented. Within only one month, the WHO had recorded more than 1,300 cases and 700 deaths, which accounts for approximately one third of all Ebola-related deaths since its discovery in the late 1970s.

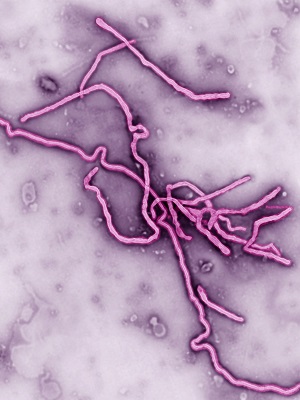

The strain at the root of this outbreak is related to the most virulent subtype of Ebola virus, known as Zaire. There is no sign that the outbreak is waning and Doctors Without Borders (MSF) says it is totally out of control.

The virus was named after the Ebola River in Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of Congo), where the disease was firstly identified in 1976. Fruit bats are the natural reservoirs to this virus. Infection is transmitted to humans via contact with infected bats, eating fruit contaminated with bat’s excreta or eating bats, which is not uncommon in certain parts of Africa. Ebola virus also infects non-human primates, which are accidental hosts like humans. Infection can also be transmitted via handling of infected wild animals or eating bush meat.

The disease presents with fever and flu-like symptoms that progress rapidly to vomiting and diarrhea. The terminal phase of the disease is characterized by internal bleeding that is accompanied, in about 50% of cases, by external bleeding from orifices.

Bleeding is a direct outcome of the body’s attempts to combat infection. It mounts an intense innate immune response that unleashes a storm of cytokines (inflammatory mediators) into circulation. This uncontrolled inflammatory response, together with the cytolytic effects of the virus (particularly on the endothelial cells lining blood vessels), increases vascular permeability, resulting in a sharp drop in blood pressure and fatal organ failure.

Until 2012, the world had witnessed 24 outbreaks of this virus, affecting mainly the central parts of Africa, with fatality rates that ranged from 60 to 90%.

The current outbreak is believed to have started in a remote village in southeastern Guinea. Unlike previous incidences, which were confined to isolated rural areas, this outbreak has crossed borders to some of the highly populous cities in neighboring Sierra Leone and Liberia.

The Middle East needs robust healthcare facilities that can treat patients without fear of spreading the disease further.

The first transmission of Ebola virus via air travel was reported last month when Patrick Sawyer, a Liberian-American patient, flew from Liberia to Nigeria. He became ill on the plane and died in Lagos from where he was returning to the US to visit his family.

This incident sparked fears of global spread of the virus. Liberia closed its schools and Sierra Leone declared a state of emergency. Neighboring countries began screening incoming passengers, others closed borders completely and some airlines suspended flights to airports in the affected countries. The US has issued a travel warning against non-essential travel to the outbreak areas.

Except for a few promising candidates and US efforts to fast track a recombinant vaccine that is yet to be tested on humans, no Ebola vaccines or antiviral drugs are currently available.

Ebola is not an airborne disease, so it does not spread easily like influenza and measles viruses. It gains access to the body through skin abrasions and mucous membranes.

Human-to-human transmission requires direct contact with body fluids and secretions of infected patients (blood, saliva, vomit, diarrhea and semen) or indirectly via touching contaminated material (such as sheets, towels, clothes, etc.).

Infected patients do not spread the disease until they start showing symptoms. Therefore, in theory, patients could be swiftly identified and properly isolated, their contacts traced and a potential outbreak would be nipped in the bud.

© BSIP SA / Alamy

The current outbreak is already moving faster than our efforts to control it, declared Margaret Chan, the Director-General of the WHO after a crisis meeting held last week in Guinea's capital of Conakry. “If the situation continues to deteriorate, the consequences can be catastrophic in terms of lost lives but also severe socioeconomic disruption and a high risk of spread to other countries,” she stressed.

While most developed countries began tightening health measures at their portals of entry, the response from the Middle East is still fairly slow.

Emirates Airlines suspended its flights to Conakry, the Lebanese government suspended the issue of work permits and the Saudi ministry of health suspended issuing Hajj and Umrah visas to residents of the three badly hit African countries. Apart from these moves, no other precautionary measures were announced.

Granted, the chance of a sick person boarding a flight is very slim, but not zero. Ebola is a disease with an incubation period that ranges from two days to three weeks. The air export scenario is highly plausible with a patient who is incubating the virus and not showing any symptoms. Therefore, screening of passengers arriving from affected countries is imperative.

If an infected patient was unknowingly transported by air, crew members should be trained to spot the disease and deal with the patient in a way that reduces the chance of transmission to other passengers. Upon arrival, the patient should be temporarily quarantined at the airport and quickly transported to a hospital equipped with isolation units. All other potentially exposed passengers should be tracked down and monitored for three weeks to make sure that they don’t show any signs of illness.

Being on the frontline, healthcare workers are the most vulnerable to infection, and therefore must be educated about Ebola symptoms and proper protocol in handling infected patients. Treating Ebola patients relies on supportive care and rehydration, and if started early enough, it could significantly boost recovery rates.

Doctors treating Ebola don head to toe protective gear, but even with this, they are still at risk. On July 29th, Sierra Leone witnessed the sad loss of Sheik Humarr Khan, who treated more than 100 Ebola patients and died shortly after he contracted the disease from one of his patients.

Hospitals with appropriate hygienic measures and isolation facilities will definitely break the disease transmission chain and reduce the grave consequences of any outbreak. The Middle East needs robust healthcare facilities that can treat patients without fear of spreading the disease further.

Diagnostic tools are also important, since early Ebola symptoms are quite generic. Without proper serological and molecular tools, Ebola confirmatory diagnosis is challenging, and shipping samples to be tested abroad is a logistical nightmare.

Finally, certain rituals of handling Ebola victims will have to be practiced with extreme caution. For instance, burial ceremonies for Muslims usually involve washing the body of the deceased by family members. Ebola virus can survive for a long time in the body of the dead patient. In the unfortunate circumstances of burying an Ebola victim, the corpse must be properly disinfected and people handling it must wear strong protective clothing and gloves.

Undoubtedly, Ebola is a deadly disease, however there is no reason to panic. Educating the public and executing healthcare preparedness plans are instrumental in containing any accidental export of Ebola virus to the Middle East.

Islam Hussein is a researcher and virologist at MIT, Massachusetts. He is currently involved in several projects focused on identifying, tracking and investigating any genetic changes that might lead to the generation of potentially pandemic influenza strains.

doi:10.1038/nmiddleeast.2014.197

Stay connected: