Using AI to control energy for indoor agriculture

30 September 2024

Published online 3 September 2014

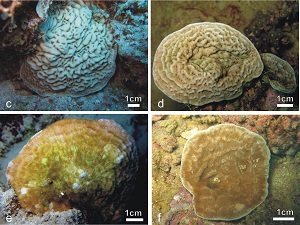

Researchers find that a previously misidentified coral is actually a new species endemic to the Red Sea.

© Francesca Benzoni

Enlarge image

The study's lead author and co-author Tullia Terraneo and Francesca Benzoni discovered the species while observing a reef-building coral through a scanning electron microscope and named it Pachyseris Inattesa for the surprised response it evoked.

Drawing a cry of “Inattesa!” (translating as “unforeseen” in English) the researchers realized that this coral, wrongly classified as belonging to the Leptoseris genus, actually belonged to the Pachyseris genus, which is not even closely related.

The confusion had stemmed from the close morphological resemblance between the two genera, which share a common yellow to brown color and wrinkly appearance. Coral taxonomy has been based for several years upon the study of macromorphological features, but due to corals’ high plasticity, traditional morphological techniques have led to many misclassifications.

“The advent of molecular techniques has led to the revision of many species and families,” says Ameer Abdulla, senior research fellow in marine conservation science at the University of Queensland, Australia.

Terraneo says the taxonomy of scleractinian corals – stony corals that generate a hard skeleton – is undergoing a “revolution” as a result of a combined approach of morphological and molecular studies. “This approach has proven very efficient in resolving species relationships within corals.”

The advent of molecular techniques has led to the revision of many species and families

Usually found between 10 and 35 metres, the new species has been recorded at different reef habitats along the coast of Saudi Arabia and so far, its distribution seems to be restricted to the Red Sea region.

Molecular techniques have shown that the degree of species' endemism in the Red Sea (at 20-30%), may be higher than previously thought, explains Abdulla. This translates into a high probability of discovering species that don't live in any other parts of the world, he says.

A collaboration between the University of Milano-Biccocain with the King Abdullah University of Science and Technology (KAUST) in Saudi Arabia that led to the discovery of Pachyseris Inattesa. It is part of a project initiated in 2012 by Michael Berumen, one of the study's co-author and the principal investigator of the Reef Ecology Lab at KAUST, to explore the biodiversity of the Red Sea.

Terraneo says new findings in the Red Sea are particularly interesting because it is a restricted biogeographic area with little connectivity to the Indian Ocean. The Red Sea presents patterns of species distribution that are not homogeneous, which alternate between areas of high and low biodiversity levels, she says. “This requires scientists' attention in order to understand the biological and climatic processes that regulate coral distribution in the Red Sea,” she says.

The Red Sea had been studied in the early days of research into coral reefs, but recent studies have been sporadic. “This is mainly due to harsh field conditions and general inaccessibility,” explains Abdulla, “coupled with a lack of scientific and taxonomic expertise in countries bordering the Red Sea and political instability.”

doi:10.1038/nmiddleeast.2014.210

Stay connected: