Using AI to control energy for indoor agriculture

30 September 2024

Published online 14 October 2014

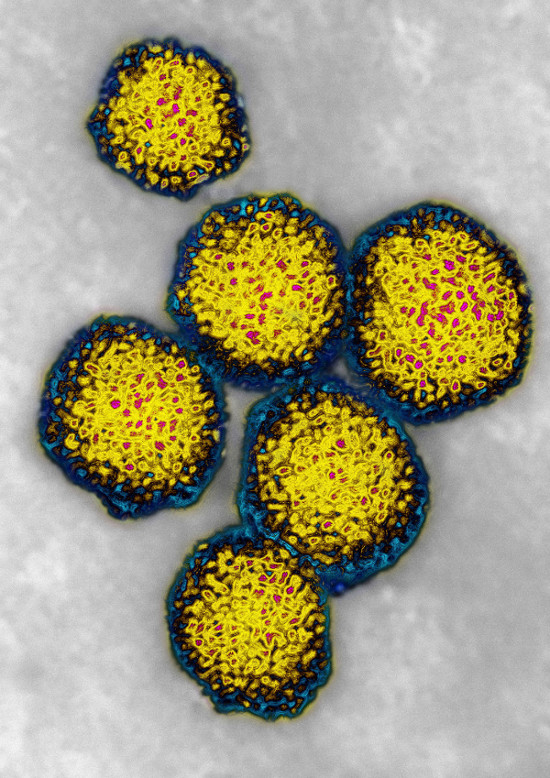

Country-wide campaigns to combat schistosomiasis in the 1960’s and 70’s may not be the major cause of the Egypt’s hepatitis C epidemic. Widespread breaches of hygiene in medical care are largely responsible.

© BSIP SA / Alamy

An estimated 14.6% of the population is infected with the virus and for decades its spread was mostly blamed on large-scale parenteral antischistosomal therapy (PAT) campaigns meant to curb schistosomiasis (bilharziasis) during the 1960s and 1970s. At the time, single-use syringes were not available, and sharing of needles led to wide-scale blood-born hepatitis C (HCV) infections, especially in rural areas.

The research published this summer by the Infectious Disease Epidemiology Group at Weill Cornell Medical College in Qatar used medical geography – a technique that maps the prevalence of a disease – combined with the results of the 2008 Egypt Demographic Health Survey to identify clusters of high and low disease prevalence. The 2008 survey is reportedly one of the largest nationally representative databases of HCV infection ever assembled.

After cross-cutting these results with the areas where the PAT campaigns had been conducted decades ago, they came to the conclusion that only 10% of current HCV infections can be attributed to them.

Statistics from the city of Suez are quite telling. Although the canal city was never targeted by the PAT campaigns back then, its current HCV prevalence is nearly as high as the national prevalence.

“For about a decade, PAT was the most accepted explanation for the unusually high HCV prevalence in Egypt,” says Diego Cuadros, lead author of the study and postdoctoral associate at the Infectious Disease Epidemiology Group at Weill Cornell Medical College in Qatar.

Cuadros says that it has been estimated that only about two million people were treated using PAT during the entire time period of the campaigns. While multiple use of syringes is an efficient mode of transmission for the virus, not all injections resulted in new infections, making it “improbable that PAT alone is the cause of the massive infection burden of this virus in Egypt.

“Most transmissions in Egypt appear to be linked to medical care.”

Wahid Doss, who is the head of the Egyptian National Committee for the Control of Viral Hepatitis and dean of the Ministry of Health's affiliated Liver Institute, was not surprised that 10% of the HCV infection can be attributed to the PAT campaigns. He stresses that the numbers may not be accurate but rather “a rough estimate.”

“We do not deny that there are ongoing infections in Egypt, it is a huge issue,” he says, adding that it stems from several main sources, including the current healthcare system.

Public hospitals and private clinics have low levels of hygiene, and the rate of transmission high, he says. “[Around] 60% of patients who undergo kidney dialysis will have contracted HCV within the year, because the machines are not sterilized properly. Same goes for blood transfusions, which are very risky.”

HCV is also contracted through male circumcision, female genital mutilation, and in barber shops and beauty salons. There are also infections that occur inside the home, he says, where HCV can be transmitted by sharing a razor blade or a nail clipper.

Wafaa El Akel, the executive manager of a network of 26 treatment centres set up by the Ministry of Health around the country, blames the skyrocketing HCV infection rate in Egypt to generally poor infection control within medical facilities, and to insufficient awareness of medical staff and of the public. “The poorer segment of healthcare professionals, like nurses, need more education to understand what HCV is and how it is transmitted, and we also need to train them on basic hygiene standards.”

However, Joachim Delville, head of Doctors Without Borders' mission in Egypt, believes that infection rates can be blamed on poor access to diagnosis and treatment, which is out of the reach of the most vulnerable, rural patients.

“The 26 centres are located in the various governorates' main cities, and we would like to decentralize the primary healthcare approach to give easier access, develop ways of diagnosis and treatment that could be more easily put in place, and in parallel decrease the treatment cost,” he says.

Doctors Without Borders is collaborating with the Liver Institute and the Ministry of Health to decentralize such treatment options. According to Delville, there is still a large gap between the number of people infected and those receiving treatment.

Doctor Without Borders' Medical Coordinator Mohamed El Tom Hamid explains that in order to decentralize effectively people need to be screened for the virus locally and treatment must be brought to where they live.

Since there are few liver specialists based in the countryside, local general practitioners need to be trained to recognize and combat HCV, he adds. “When you have a high prevalence of HCV like in Egypt, it is cost-effective to decentralize,” he adds.

Cuadros hopes that the results of this study will lead to a more specific and efficient response focused on areas that have intense HCV transmission rates “[This] is likely to be more cost-effective than a broad one at the national level.”

“Our study delineates the areas suffering the highest infection burden, where resources such as HCV treatment, infection control, and proper sterilization, among other prevention measures should be prioritized,” he says.

doi:10.1038/nmiddleeast.2014.246

Stay connected: