Using AI to control energy for indoor agriculture

30 September 2024

Published online 14 November 2014

Doctors and researchers say that type 1 diabetes is rapidly on the rise in the Middle East and call for intervention to stop it from spiraling out of control.

© Louise Sarant/Nature Middle East

Official registration of type 1 diabetes cases is inadequate in Arab states, but many healthcare practitioners and researchers argue that incidence of the disease is rising sharply.

More alarmingly, the incidence among infants is growing with children developing the disease as early as six months, rather than the established peak ages of around seven and at puberty, when hormones antagonize the action of insulin.

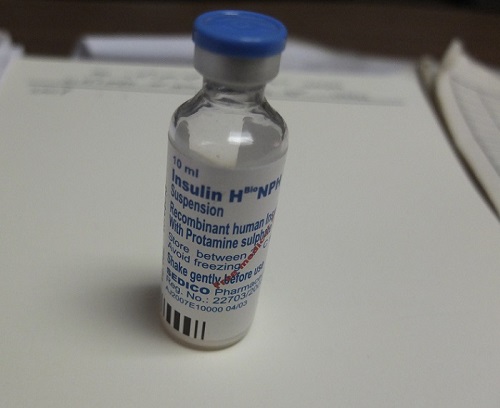

In type 1 diabetes cases, the pancreas produces little to no insulin, leaving patients dependent on daily insulin injections to maintain their blood glucose levels. Unlike type 2 diabetes which is often caused by an unhealthy lifestyle, type 1 origins are mostly speculative.

Genetics seem to play a role in the development of the condition, as well as autoimmune and environmental factors such as pollution, toxins and viruses. “Sometimes a child's type 1 diabetes appears following a viral infection like hepatitis,” says Mona Elsamahy, head of the Pediatric Diabetes Clinic at Ain Shams Children's Hospital.

Elsamahy’s department treats and supports about 2,000 children. Her desk is piled with healthy eating booklets in Arabic with colorful depictions of the different food groups and how to balance them well. “We also have drawings that show how to give insulin injections and use the insulin pens, in order for illiterate parents to follow the procedure,” she says.

While there is no national registry in Egypt, each centre tries to maintain a database, adds Elsamahy. “The prevalence of type 1 diabetes is growing at alarming rates,” she contends, stressing that her centre received 200 new patients in the past two months. Although figures are incomplete, she estimates that every school in Egypt has at least one diabetic child.

In other Middle Eastern countries, the number of incidences per 100,000 people varied from 2.5 in Oman to a 22.3 in Kuwait. The highest rate in the region was in Saudi Arabia, with 14,900 children with type 1 diabetes, approximately a quarter of those in the Middle East and North Africa. This is comparable to numbers in Norway and other Scandinavian countries, where type 1 diabetes is historically and genetically more prevalent than in the Middle East, Asia and Africa.

“We don't truly know what the incidence in Arab countries is,” explains Shahrad Taheri, professor of medicine at Weill Cornell Medical College in Qatar. “Accurate diabetes registries don’t exist and in countries with a large expatriate population, it is difficult to separate data for the indigenous population.”

Taheri suggests the rising incidence of the disease in the Middle East is mainly due to rapid lifestyle changes, such as “change in nutrition, especially in the first years, changes in breastfeeding practices, environmental pollutants and toxins, autoimmune deficiency caused by greater hygienic standards and low vitamin D levels, which are highly prevalent in the region in spite of the sunshine.”

In the past years it has become very difficult to get public funds.

Researchers in laboratories around the world are looking to stem cells as a possible cure for type 1 diabetes. Nermeen Youssef, an Egyptian scientist from the University of Alberta in Canada, presented her research on type 1 diabetes at the Falling Walls scientific conference in Berlin this week. Youssef and her team are trying to engineer fat cells to produce insulin.

“30 million people get poked by needles every day, and insulin injections produce fluctuating levels of sugar in the body,” says Youssef.

Elsamahy, however, is not convinced of the feasibility of Youssef’s theory. “The initial problem with type 1 diabetes is the fact that the immune system attacks insulin-producing cells. I don't see why the same autoimmune reaction would not destroy these engineered cells when they are reintroduced in the patient.”

Bahaa Gordon, an Egyptian endocrinologist with the Egyptian Diabetic Care Association, is treating a growing number of children with type 1 diabetes at three clinics across the country. “We had doctors in small centres all over Egypt, but in the past years it has become very difficult to get public funds and we have a hard time finding candidates,” he says.

The Egyptian health ministry provides intermediate-acting insulin at a subsidised cost less than US$1 per vial, but both Elsamahy and Gordon say it is a poor alternative to rapid-acting and baseline insulin, the preferred newer regimen around the world. “In my department, we try to give children the highest quality insulin as often as we can, but we rarely have enough for everyone,” says Elsamahy.

A lack of public funds mean most attempts put in place by physicians like Elsamahy and Gordon at education or control of type 1 diabetes are self-funded or supported by pharmaceutical companies. Elsamahy and her team often take children on excursions where they can play and become aware of how exercise lowers their blood glucose levels. “It is much more efficient for them to realize the link between exercise and sugar levels on their own,” she says, adding that these activities enable parents to ask questions about their child's condition.

doi:10.1038/nmiddleeast.2014.266

Stay connected: