Using AI to control energy for indoor agriculture

30 September 2024

Published online 2 April 2014

The outcome of the uprisings across the Middle East and North Africa may be uncertain, but what is clear is that a political transformation has taken place. People in countries such as Egypt and Tunisia will not allow a return to totalitarian governance. Not only can they demonstrate and bring down governments — they will no longer tolerate a degraded economic and educational status. Through social media and the Internet, they 'see' the world and ponder why they have not achieved what their counterparts in South Korea or China have. Pundits may argue that the outcome of these uprisings should be democracy, but equally important are the scientific and cultural transformations that are essential for development and diplomacy to flourish. Let us recall that in the evolution of Western civilization, the Enlightenment came ahead of modern democracy, and both before the current governance structure and social order.

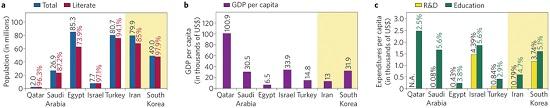

I have been concerned with these issues in the Middle East for decades — in official and non-official capacities — and their relevance to a 'science for the have-nots' vision, which addresses the mission of aid programmes and diffusion of science in developing countries. In November 2009 I was asked to be the first US science envoy to the Middle East and soon after I began the inaugural mission, visiting Egypt (the most populous country in the Arab world at 85 million with a gross domestic product (GDP) of US$6,500 per capita), Turkey (80 million people of Middle Eastern, but non-Arab, descent and a GDP of US$15,000 per capita) and the Gulf state of Qatar (2 million people with nearly 0.3 million Qataris and a GDP of US$100,000 per capita). Figure 1a,b shows the total population, literate population and GDP of these countries, as well as those of Iran (whose population is similar to Egypt) and South Korea (an Eastern Asian country with a GDP remarkably higher than that of Egypt, and which has shown a significant scientific development in the past few decades).

The meetings were broad-ranging and included visits with government officials (heads of state, prime ministers, ministers and some members of parliament), members of the education sector (teachers, students and university professors), institutions of higher education and research (private and state universities), members of the private sector (economists, industrialists, writers and publishers) and some media representatives. These visits exposed the plight of education and science in the region, which lags behind international standards (the consequences are clearly spelled out in the 2003 Arab Human Development Report sponsored by the United Nations Development Programme). The data are telling: whereas the expenditure in research and development (R&D) of South Korea and Israel reaches 4% of the GDP and both countries spend 5% of their similar GDP (US$30,000 per capita) in education, Egypt's R&D expenditure is 0.4% at a GDP of US$6,500 per capita (Fig. 1b,c). The current situation is in sharp contrast to the system of schools and universities that existed even in the 1960s, when I benefitted personally from an excellent education in Egypt.

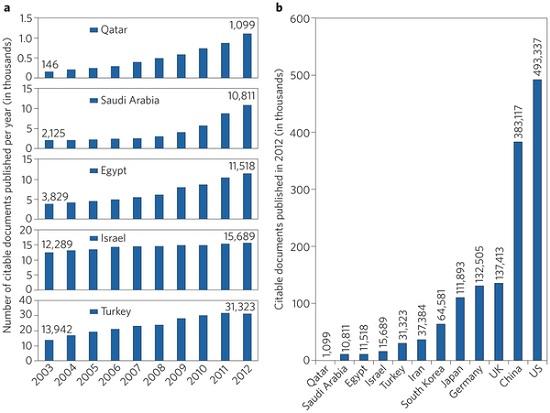

In the Middle East, Israel leads today in scientific impact, and a major part of its GDP is science-driven. In general, publication and citation indicators show some encouraging trends for the region over the past decade (Fig. 2). However, the impact of scientific research in the Arabian, Persian and Turkish Middle East still pales to that of Israel and the West, and it is natural to ask why the scientists have, as a group, underperformed compared with their colleagues in the West, or with those rising in the East. The reasons are numerous. In the Arab world they include the illiteracy pile-up during colonization, the poor governance and imposed deprivation of free thinking over the past half century, and the continued deterioration of core education owing to the ineffective policies of handling a large student population.

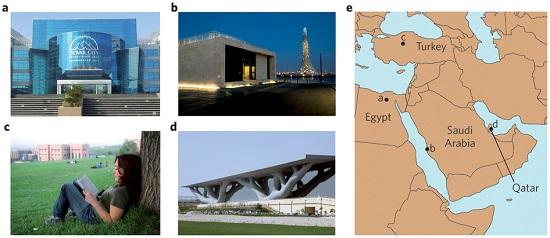

Beyond the causes of the current state of affairs, it is important to understand what is being done to change this situation. The approach varies, depending on country. Here, I shall consider four centres, highlighted together with their geographical positions in Fig. 3, which are already operating in countries where Islam as a culture is the major religion.

Images from: a, © Zewail City of Science and Technology; b, © Flickr Vision/Getty; c, © Caro/Alamy; d, © philipus/Alamy.

In the Gulf, I have served on the Board of Directors of the Qatar Foundation for nearly a decade, during which time I witnessed the birth of a new experiment in university learning; namely, the transfer from the West of established university systems offering cutting-edge education curricula to students of the region. Today, there exist many reputable schools that are sponsored by the Qatar Foundation, and these include Carnegie Mellon University for degrees in computer or biological sciences, Weill Cornell College for medical degrees and Georgetown University for degrees in international affairs or international economics.

These and other universities are granting degrees in Doha marked with the institutional insignias of their Pittsburgh, New York and Washington DC campuses. The experiment is very costly to Qatar, but for its purpose it is a successful one, as it brings a new culture of learning to this and nearby countries and defines new standards in higher education. At the moment these institutions serve a relatively small population, but with time the opportunity exists for a much larger student body, as both space and funds have already been endowed for the foundation.

At the graduate level, two institutions in Turkey and Saudi Arabia provide different structures and may make scientific impact by different means. Bilkent, or City of Science, is the first private university in Turkey. As a 30-year-old institution, it has established itself as a leader in undergraduate education and graduate research, and is ranked as one of the best educational institutions in Eurasia. While visiting Bilkent, I was impressed by the high density of world-class faculty, the culture of the place and the drive to achieve at the highest scientific level. Turkey has the necessary human resources and Bilkent is able to attract the best students and faculty.

King Abdullah University of Science and Technology (KAUST) in Saudi Arabia is another institution in the region that focuses on research and development. The vice president of KAUST, Jean Fréchet, provides in Nature Materials the perspective of the administration and what is hoped for in the future. More than US$10 billion has been committed to this Saudi project. Most of the staff and administration are brought in from outside the Kingdom. Surely there will be research output in the coming years, in diverse and important areas, with new opportunities. The real challenge is how to disseminate this new science culture throughout the country, beyond the premises of KAUST, and how to make it attractive enough to Saudi nationals so as to secure continuity and sustainability.

In Egypt, a different course has been taken — one that I have personally charted for more than a decade. The concept of the project was outlined in 1999 to the then president of the republic, but owing to political reasons, implementation was halted. After the revolution of January 2011, the project was revived and the Egyptian government decreed its establishment as the national project for scientific renaissance, naming it Zewail City of Science and Technology. The City was inaugurated in November 2011 on a campus on the outskirts of Cairo.

The project is unique in several respects. First, in an unprecedented way — certainly in Egypt — the City is supported by donations from the Egyptian people and from the government. Second, the City has its own special law, granted in 2012, which allows for independent governance by a board of trustees that includes five Nobel laureates. Third, the City comprises three interactive substructures: the university, the research institutes and the technology pyramid, designed to enable world-class education, scientific research and industrial impact. The goal is to build a modern science base with an advanced industry sector and, as importantly, to limit the brain drain in these advanced fields of science and engineering.

The prime purpose of the university is to attract talented students from all over the country and to offer them unique academic curricula that are tailored to provide knowledge in cutting-edge fields of science and engineering. The new concept here is the departure from traditional departments with walls separating the disciplines. Rather, all students have the opportunity to learn in a multidisciplinary, or transdisciplinary, system. This year, 6,000 students applied for admission and 300 were admitted — a 5% admission rate that is on a par with Harvard and Yale.

The second branch of the City, the research institutes, houses centres in fields at the forefront of science and engineering. Priority is given to research particularly pertinent to national needs. The scope of research is broad, from biomedical sciences — which are important for alleviating diseases of the region — to R&D in areas such as solar energy (an alternative source abundant in Egypt). At present, we have seven centres of research in fundamental physics, materials science, nanotechnology, imaging and biomedical sciences, among others. The last substructure is the technology pyramid, whose purpose is to transfer the output of the research institutes to industrial applications, to initiate incubators and spin-off companies, and to attract major international corporations.

These centres of excellence in the region have the potential to transform the overall state of science and the culture of learning. However, in countries rich with human capital but poor in governance and literacy, other revolutionary changes must be implemented.

First, the eradication of illiteracy and the building of human capital with the participation of women in the work force are paramount. The current education system is based on rote learning with a focus on quantity rather than quality and this must be replaced with a system that is merit-based and aimed at encouraging free and creative thinking.

Second, the reform of the constitution is essential to allow for freedom of thought and the insulation of scientific enquiry from political and religious interference. The constitution should also state that governments must increase funding of R&D to at least 1% of the GDP and decrease bureaucracy by reforming obstructive laws and regulations.

Third, and perhaps most difficult, is cultural reform. After decades of poor governance and religious conflicts, there is a dire need for a change in thinking, from intolerance to tolerance of others and their opinions, or simply towards understanding the virtues of pluralism. Without a healthy education system and enlightened centres of excellence, the hope of making such changes is dimmed by the use of political manoeuvres and religious hindrances.

Egypt was and still is the leader of the Arab world. Its next revolution in education and culture will trigger major changes in other Arab countries. Even though this leadership role has slipped over the past three decades during Mubarak's reign, Egypt still has the history and the foundation, not to mention the population and institutions, to regain the avant-garde force of the necessary transformation. Egypt pioneered democratic governance in the region through parliamentary elections, a practice the country is struggling to continue today. More than a century ago, numerous industries emerged including banking, mass media — such as the well-known Al-Ahram newspaper — textiles, motion pictures and others. With such achievements, Egypt at that time was ahead of South Korea and Japan in management, education and related fields. Today Egypt is the home of Al-Azhar University (which is older than Oxford and Cambridge) and Cairo University (a centre of enlightenment not only in Egypt but also for the whole Arab world). So the potential for change and rebuilding is real.

The Middle East, with all its resources, is no less capable of development than Southeast Asian countries. The human capital is available and a major fraction of the population is young (nearly 70% of the population is under 30 years of age ,). The region is also rich in natural resources, enjoys a moderate climate and the people are culturally inclined towards hospitality and commerce.

The deficits of the region — which the 2003 Arab Human Development Report identifies as freedom, knowledge and gender gap2 — can be remedied through education and governance reforms, as outlined above. Education and research reforms must go beyond the failed patching policies that have been made in past years; they must foster creative thinking and innovation as well as encourage curiosity-driven research,. Furthermore, they must instil the meaning of citizenry, which will not be acquired without appreciation for the value of free debates, team work and respect for pluralism.

Arab awakening is a reality, but political conflicts in the region obscure its potential. Here, also, education and science can play a key role in diplomacy and the acceleration of the peace process. Once Arabs realize scientific achievements through a transformative educational and cultural process, and when countries such as Israel realize the potential of such achievements, a more rational and serious dialogue for diplomacy and a comprehensive and just peace will divert the energy of the region towards human and economic developments.

The hope is that the political awakening already in motion in the region will support a successful 'science spring' that sweeps the Middle East and enables the building of a knowledge society. Knowledge acquisition is a concept that is woven into the fabric of Islam and was the springboard of success of its empire centuries ago. But to regain prominence in today's world, that concept must re-emerge, transforming the culture in ways necessary for the charting of a new and promising future.

doi:10.1038/nmiddleeast.2014.86

Stay connected: