Using AI to control energy for indoor agriculture

30 September 2024

Published online 22 June 2015

Researchers in the Arab region are turning to an old adversary of bacteria in the hope of finding an alternative for antibiotics.

For a short time, bacteriophages showed promise as an antibacterial therapy. But with the advent of antibiotics some 15 years after d’Herelle’s discovery, most of the Western world shifted its focus to antibiotics, largely abandoning bacteriophage research.

But in April, the World Health Organization (WHO) rang alarm bells, warning that overuse was leading to a future of antibiotic resistance.

Among Arab states that had data to provide, none reported having a national action plan for antimicrobial resistance, while antibiotics were reported to be available without a prescription in nine out of the 21 countries belonging to the WHO’s Eastern Mediterranean Region.

Among those countries is Egypt, and the misuse of antibiotics causes concern for a few Egyptian researchers who looked to bacteriophages as an antibiotic alternative.

“So many times I have talked to the Science & Technology Development Fund (STDF) and the [Academy of Scientific Research and Technology] about the need to put a lot of funds into bacteriophage research in Egypt,” says Ain Shams University agricultural virologist Tarek El-Arabi, “because the excessive use of antibiotics to control bacterial diseases in animals is out of control now.”

The STDF has granted 1.5 million EGP (~US$200,000) to a project at Zewail City of Science and Technology, just outside Cairo, to develop a bacteriophage-based tool that can detect and identify pathogenic bacteria in samples from the food chain and hospitals.

The excessive use of antibiotics to control bacterial diseases in animals is out of control now.

Also, Egypt’s Academy of Scientific Research and Technology, through its EU-funded Research, Development and Innovation Programme, has granted El-Arabi’s laboratory €444,000 to find natural antagonists to a large variety of pathogens that infect tomato and potato plants in Egypt. As part of this project, El-Arabi and his team, in collaboration with German and Austrian institutes, have isolated bacteriophages and are testing them against the bacteria Ralstonia solanacearum and Salmonella.

El-Arabi is also supervising several other bacteriophage-related postgraduate research projects. One Masters student is using a phage coat to protect the bacterium Rhizobium, which is beneficial to legumes like beans and lentils, from bacteriophage attack. They are blocking receptors to which phages normally bind so “that when wild phages come across the bacteria in the environment they would not be able to bind to the host,” explains El-Arabi.

Another student is collaborating with a colleague at Canada’s University of Guelph to isolate phages they hope can control Clostridium difficile, a very resistant bacterium that affects the digestive system.

El-Arabi also collaborates with Ayman El-Shibiny, a microbiologist at Zewail City’s University of Science and Technology. El-Shibiny’s laboratory has specifically dedicated its research efforts to studying bacteriophages.

“We have a very serious problem in Egypt with antibiotic resistant bacteria,” says El-Shibiny. “We must enforce regulations against selling antibiotics without prescriptions and form a network to link all hospitals in Egypt to identify any outbreaks and any pathogenic bacteria,” he urges.

El-Shibiny is isolating phages from the surrounding Egyptian environment, hoping to find bacteriophages specific to bacteria in the country. He aims to establish a phage bank at Zewail City and to create the first dedicated research centre in Egypt and the Arab region to do phage therapy, he says.

In addition to his STDF-funded project to use phages as a quick detection tool for pathogens in the food chain and in hospitals, El-Shibiny is also working on creating a mix of phages that can be applied to patients with wound infections and with diabetic foot, a dangerous infection in diabetics that can lead to gangrene and force amputation.

Further north in Egypt’s fertile Delta region, Ahmed Askora, a microbiologist at Zagazig University, has been isolating bacteriophages from hospital waste water to target Pseudomonas aeruginosa, a bacterium that can cause life-threatening infections in humans.

Askora successfully tested his bacteriophage on rats infected with the bacteria and is in the final stages of genome sequencing of the bacteriophage at Paris-Sud University in France to identify the specific genes responsible for killing the bacteria. “The full genome sequencing requires very specific equipment that is not available in Egypt,” explains Askora.

By identifying the gene responsible for bacterial lysis, Askora hopes to use it to develop a therapeutic product for commercial use, a goal that is still several years away.

The full genome sequencing requires very specific equipment that is not available in Egypt.

Microbiologist Ramy Aziz from Cairo University’s faculty of pharmacy is particularly interested in the phase of bacteriophage research that follows genome sequencing. He was involved in the development of PhAnToMe (phage annotation tools and methods), a bacteriophage database created in the US between 2009 and 2012.

Funding for the database has ended, but it continues to be updated and it now holds the genome sequences of more than 2,000 bacteriophages, making it one of the most comprehensive phage databases available, according to Aziz.

PhAnToMe includes a tool that helps identify phage genomic material that has been injected inside a bacterial genome. Aziz’s role in the development of this tool was to help the software developer “teach” the programme how to distinguish phage genomic material with a reasonable degree of accuracy.

Aziz trains scientists across the world on phage genome analysis as one of the few experts in this area. He is also passionate about training his students at Cairo University to use computer programmes to identify phage genomic sequences. Genome analysis requires a lot of knowledge and many human resources – something Cairo University’s large student body can amply provide, he says. Aziz was recently part of a large international team that discovered2 the most abundant virus in the human intestine, crAssphage, which they believe takes the bacteria Bacteroides as its host.

Egypt does seem to be a growing epicentre of bacteriophage research, but there are scientists in other parts of the Arab world showing interest in the area – despite negligible networking between them.

At Carnegie Mellon University in Qatar, biochemist Annette Vincent and her undergraduate student Umm-Kulthum Umlai were surprised to successfully isolate a bacteriophage that targets Athrobacter woluwensis from the dry, arid sands surrounding the university. This bacterium is used for denitrification and dephosphorylation in waste water treatment, before it is normally killed off by large quantities of chlorine. Vincent hopes that their bacteriophage could provide a safer alternative to chlorine in wastewater treatment in Qatar.

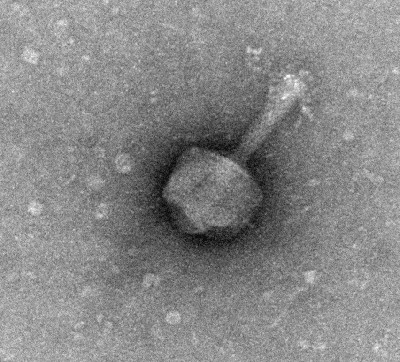

© Ayman El-Shibiny

This field of research continues to grow in the region, with other countries, such as Tunisia and Saudi Arabia, also running research programmes on bacteriophages.

El-Arabi says the Egyptian Society for Virology hopes to organize a session on bacteriophage research in its next biannual Arab regional conference at the end of 2016. He hopes this will open the door for better networking between Arab scientists doing research in the field. “We have no idea who is doing what,” he says. He explains that many researchers in the Arab region publish their work in local journals that other colleagues in the region do not have access to. It is usually only when research reaches the higher impact journals that colleagues can become aware of their work. In the case of bacteriophage research in the region, publishing at this level is still limited.

El-Arabi believes Egypt can be a “nucleus for bacteriophage research” as the country’s laws and regulations allow for animal and tissue culture experiments that are more difficult to conduct under the legal systems of European countries. “For instance, we don't have a specific limit for the number of trials or the number of animals used in each trial as long as other ethical points of animal welfare are covered,” he explains. “Secondly, for field applications, many farmers are usually willing to allow us to try new methods to control plant bacterial pathogens.” This allows, he explains, for studying the toxicity of bacteriophages and their impact on disease.

El-Arabi believes it would be beneficial for Egyptian researchers interested in bacteriophage research to collaborate in a single large study, the results of which could eventually be presented to government officials to convince them of the importance of this area of research.

He says that the absence of a regulatory mechanism to approve the licensing of bacteriophage products will also need to be addressed at the appropriate time.

doi:10.1038/nmiddleeast.2015.102

Stay connected: