Using AI to control energy for indoor agriculture

30 September 2024

Published online 21 June 2017

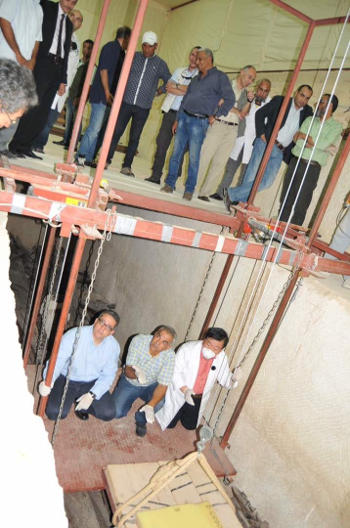

Inside one of the world’s largest onsite archaeological labs.

© Khufu Second Boat Project

This is no ordinary excavation; the wooden pieces from the 42-meter-long boat are so delicate that the archaeologists cannot simply remove them from the ground without extensive onsite conservation.

It’s the reason why the team – funded by Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) – has built the Giza Second Solar Boat lab, one of the world’s largest onsite conservation labs to save this ancient ship.

Archaeologists have known of this boat’s existence since 1954, when an Egyptian team found two pits during cleaning, according to Mamdouh Taha, project supervisor and chief inspector of excavations at the Giza plateau. Both pits contained one carefully dismantled wooden boat, stacked neatly, with hieroglyphics directions inscribed on the planks. Ancient Egyptians beliebed the inscriptions helped reconstruct the boats in the afterlife.

Before a single piece of wood could be removed, the team needed to create a comprehensive conservation plan.

Given its better preservation, the earlier archaeologists chose to excavate the first boat – that is now on display in the Solar Boat Museum at Giza.

As Taha points out, these boats are the only objects ever found that definitively belonged to Khufu, the builder of the Great Pyramid, making these boats historical important.

The boat’s fate changed in 1987, when the National Geographic and the Ministry of Antiquities drilled a tiny hole through the second pit’s limestone cover and sent a small camera on an exploratory mission.

“When they put the camera inside they were astonished … because they found some black beetles moving. It meant that there were cracks, giving insects the chance to get inside,” Taha says.

The boat was also damaged by water that might have leached in from the construction of the Solar Boat Museum only a few meters away, according to Eissa Zidan Abd ElBadie, supervisor of conservation at Khufu Second Boat Project and general director of first aid conservation at the Grand Egyptian Museum (GEM). These cracks also altered the pit’s temperature and humidity, further destabilizing the boat.

Khufu’s second boat was in a dire situation until 2009 when Waseda University – with JICA funds – approached the Ministry of Antiquities with a plan to save the boat. With technological advancements in materials conservations and a steady stream of funding, the ambitious plan to save Khufu’s boat began.

© Khufu Second Boat Project

The boat pit’s climate is completely different from the surrounding Giza plateau, explains Youssef Khaled, the project’s chief engineer. The constant humidity is 90% inside the pit and the temperature is 25–26°C.

Ancient wood is very sensitive. Fluctuating temperature and relative humidity is a fundamental reasons wooden objects deform and crack because of swelling and shrinking, says Eman H. Zidan, archaeological conservator at the Ministry of Antiquities.

Working without heavy equipment to protect the site, the team hand-built a 35m-wide and 6m-tall hanger with two buffer zones, covering the boat pit, in addition to a conservation lab. Once work got underway, archaeologists began to uncover planks of wood over 20m-long, which necessitated building larger lab that was opened in March 2017.

Before a single piece of wood could be removed, Eissa and the Japanese team needed to create a comprehensive conservation plan. The preparation work was extensive, they say.

The team performed radio carbon (C14) dating, identified the types of wood, and analyzed pigments from paint. Once the materials were identified, conservators carried out experimental studies to find the best methods of conservation. As ElBadie says, “We can’t apply any materials directly without an experimental study” to know how it would impact the wood.

Next, the team consolidated the wood fragments inside the pit, with each individual piece numbered, photographed, and coated in a protective material. Once the fragments were lifted with a special crane, the conservation team had to do a full evaluation of each piece, says ElBadie.

Since 2009, the team has removed around 700 wood pieces from the pit. Based on the amount of fragments from the first boat, the team estimates that this constitutes more than half of the boat.

Conservators painstakingly cleaned each individual piece, filled in gaps with conservation materials, and re-joined broken fragments. The work is usually slow, ElBadie explains; it takes the team roughly one month to stabilize a 20m plank of wood for transport to the GEM.

The ultimate goal of the project is to reassemble the boat, so with this in mind, the team takes a 3D laser scan of every piece of the boat. This will allow the GEM conservation team to re-assemble the boat digitally in a 3D puzzle, without handling the wood and risking further damage.

The results, however, are usually astounding, as per the scientists.

Removing a layer of protective covering, ElBadie showed me a conserved plank of wood that looked as if buried yesterday. Placing his gloved finger on the plank, ElBadie explains, “Before consolidation, if you touched it, it would break. Now you can touch it, it’s very strong.”

doi:10.1038/nmiddleeast.2017.109

Stay connected: