Using AI to control energy for indoor agriculture

30 September 2024

Published online 16 August 2017

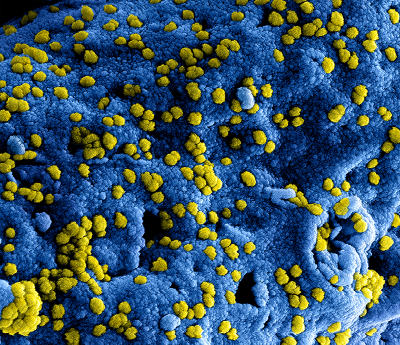

This first-ever analysis of blood cells from Middle East respiratory syndrome survivors highlights their immune response to the disease.

© National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID)

Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) is caused by a coronavirus (MERS-CoV), which is transmitted via dromedary camels or from other people. It can lead to severe pneumonia.

The World Health Organisation revealed that there were more than 730 deaths caused by MERS, as of July 21, 2017, with 81 new cases identified in Saudi Arabia in 2017. The disease is considered a significant health threat, with the potential to become an epidemic, making it a prime target for vaccine development.

Conducting MERS research can be challenging given the small number of infected patients in the Arabian Peninsula, the many obstacles to obtaining samples through the Ministry of Health, and what some researchers have termed the “self-stigmatization of MERS patients” preventing study enrolment.

These hurdles have hampered a full understanding of the immune response in MERS.

But Jingxian Zhao, Abeer N. Alshukairi, and colleagues, however, were able overcome some of these challenges in their new study1, helped by Alshukairi’s affiliation with the King Faisal Specialist Hospital and Research Centre.

MERS survivors (even those with mild or asymptomatic infection) demonstrated MERS-CoV-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cell activity. Thus, the T cell responses in exposed populations can more accurately estimate the prevalence of MERS.

Some neutralizing antibodies from the patients’ sera, which correlated with antiviral protection in mouse models, also have the potential to act as vaccine targets. Moreover, the CD8+ T cell count was maintained in patients who most effectively fought the virus (even in the absence of neutralizing antibodies), suggesting that it might be more useful for predicting positive patients’ outcomes compared with antibody levels alone.

This study highlights MERS-specific markers, which could be tested to lead to a better prognosis. It also offered insight into developing a vaccine against MERS, which Stanley Perlman, a senior author on the study, says “should induce both an antibody response and a T cell response.”

Pritish Tosh, an infectious diseases physician and researcher at Mayo Clinic, who is not affiliated with the study, states that “it is a significant step in the understanding of the basic immunology of this infection, which is necessary for the development of an effective vaccine.”

The authors hope to extend the study to a larger patient sample, and people who work with camels, but do not show MERS symptoms.

doi:10.1038/nmiddleeast.2017.125

Stay connected: