Using AI to control energy for indoor agriculture

30 September 2024

Published online 30 November 2017

Humans are “voracious users of artificial lighting” and it’s getting worse.

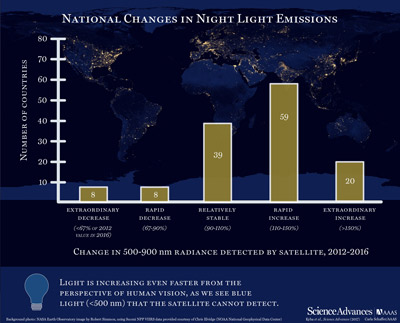

At a conservative estimate, artificially lit areas on the Earth’s surface have been growing at a rate of 2.2% per year between 2012 and 2016, according to the authors of a new study published this week in Science Advances.

Despite the fact that more cities have switched from sodium lamps to LEDs for street lighting to save energy, new or brighter lights in other places are offsetting these savings.

“We might have hoped that the growing availability of highly efficient, solid-state LED lighting technologies might contribute to a decrease in energy usage worldwide,” says Kip Hodges, co-author and professor of earth and space exploration at Arizona State University. “Instead, it appears that the use of artificial lighting is expanding rapidly, regardless of the lighting technologies used, in ways that undoubtedly increase energy demand.”

Human use of artificial lighting is “voracious” and a global decrease in energy consumption is highly unlikely, say the scientists.

According to Hodges, night-time radiance creates negative effects on our health, ecosystems and astronomical research.

Variations in light and darkness triggers a wide range of processes from gene expression to ecosystem functions, according to Franz Hölker of the Leibniz-Institute of Freshwater Ecology and Inland Fisheries.

For humans, a spike in nighttime radiance will impact sleep. More use of LED lights means organisms are more exposed to the blue light in the spectrum, which can have negative consequences for wildlife, especially insects and mammals. As well, artificial light emissions erode the Earth’s remaining land areas that experience natural day/night light cycles.

Hölker says that such changes in skyglow and radiance threaten about 30 percent of nocturnal vertebrates and more than 60 percent of invertebrates.

Changing night habits can affect biodiversity as well as reproduction or migration patterns of many different species; insects, amphibians, fish, birds and bats. “Artificial light is an environmental pollutant with ecological and evolutionary implications for many organisms –– from bacteria to mammals, including humans –– and may reshape the entire social ecological system,” says Hölker.

The scientists measured the change in light emissions from October 2012 to October 2016, using the Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer or VIIRS Day/Night Band, a sensor mounted on a polar-orbiting satellite called Suomi NPP.

Suomi NPP circles the Earth from pole to pole about 14 times a day. Each orbit has an ascending and a descending side “and it’s the descending side where we collect the nighttime data,” explains Kimberly Baugh, co-author and professor at the Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences (CIRES) at the University of Colorado Boulder.

The study comes with caveats: the first is that radiance varied greatly by country, for instance, artificial light growth in developing countries in Africa, Asia and South America is much faster than in areas that are already very brightly lit, like the United States, and the second is that VIIRS does not see blue light.

“When we switch from orange lights to white lights that include a lot of blue, we don’t see all of the light that a human eye would,” says Christopher Kyba, co-author and remote sensing specialist at the German Research Center for Geoscience (GFZ). “That means that this measurement that we’re reporting is a lower bound on how Earth’s light is increasing.” In other words, in reality, the problem might be worsening at a much faster pace.

doi:10.1038/nmiddleeast.2017.164

Stay connected: