Using AI to control energy for indoor agriculture

30 September 2024

Published online 28 January 2017

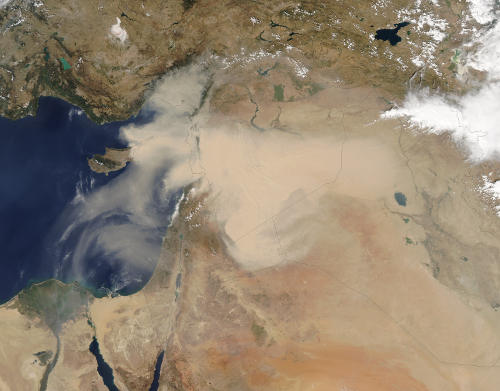

The shamal of 2015 was down to hot dry weather and unusual easterly wind patterns, not war in Syria. But is this a sign of things to come?

© NASA

But this hypothesis, it seems, was premature.

Scientists unravelling the data have drawn less dramatic conclusions: a very dry, hot summer and unusual easterly winds are behind the phenomenon.

Their work, published in Environmental Research Letters, gauged the difference in land usage over the preceding 15 years by analysing remote sensing satellite information about green cover, or Normalized Difference Vegetation Index. They found that not only was agriculture robust in that year, but vegetation cover was nearly double the average of the drought years of 2007-2010.

Their analysis of meteorological data and wind speeds showed how extreme high temperatures and low humidity in August lowered the threshold for wind erosion, creating the perfect conditions for dust emission. Weather Research and Forecasting model simulations indicated a cyclonic pattern originating in Syria and northern Iraq that was standard for the time of year. However, they revealed a late change in wind direction at low levels that carried dust far west to the Mediterranean Coast, instead of east.

"Our region will need to develop environmental policies and plans that take into account new realities."

“Intuitively, the claim that the [Syrian] conflict was at the origin of such an extraordinary event was questionable. We showed the storm was largely due to historically unprecedented aridity and unusual weather conditions,” says author Shmuel Assouline, an environmental physicist at the Agricultural Research Organisation, Volcani Center, Israel.

In the context of climate change, however, this is no mundane observation.

“Our fine-resolution climate simulations within the international Coordinated Regional Climate Downscaling Experiment (CORDEX) project show that the surface air temperature in the Middle East and North Africa will increase by 1.5 Kelvin by 2050. As precipitation does not show any significant trend, it implies increased aridity that will translate into more dust generation,” says Georgiy Stenchikov, Earth Sciences and Engineering Program Chair at KAUST, Saudi Arabia, and a contributing author to the IPCC’s Fourth Assessment report.

Connecting aridity and the generation of dust in the 2015 shamal, he says, fits with other recent studies of the Middle East, including Klaus Klingmuller’s 2016 region-wide analysis, which related the development of high atmospheric aerosol concentrations in the past 15 years to soil dryness.

“There has been a rise in the frequency and strength of dust storms in the region over the past few decades,” says Alaa Ibrahim, professor of astrophysics and director of observatory, Zewail City of Science and Technology, Egypt. As celestial observation is fundamentally affected by dust, Ibrahim is now part of an ongoing project mapping aerosol dynamics over Egypt.

“Our region will need to develop environmental policies and plans that take into account new realities,” he said. A key component of that, he says, involves governments and researchers worldwide freeing up access to real-time air quality data.

It is not just the Middle East that has seen an increase in dust storms in recent decades.

In China, dust storms were so severe that the government invested in large-scale tree planting efforts in Inner Mongolia. This, according to a 2016 paper in Science, has reduced the problem there for now. The China model shows is that, with intelligent policy design, improving ecosystems can co-exist with economic growth.

Robert Costanza, leading ecological economist and chair of public policy at the Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University, addresses this interdependence of human economies and natural ecosystems.

Ecosystems, he says, contribute to human well-being in a number of complex ways, including providing agricultural products, clean air, fresh water, disturbance regulation, climate regulation, recreational opportunities, and fertile soils.

Land degradation reduces the productivity of ecosystems and therefore the value of the services they provide. Work published last year in Ecological Economics shows that the economic costs of this loss are high, amounting to $6.3 trillion a year or 10% of global GBP in 2010.

Among the 10 countries with the highest percentage levels of land degradation mapped were Tunisia (53.8%), Libya (43.7%) and Iraq (40.7%).

The 2015 Middle East dust storm, Costanza says, is “one more example of how climate change is increasing the frequency and severity of extreme weather events, compounded by longer-term land use practices that expose bare soil and strip vegetation. The costs of these kinds of events are going to escalate quickly.”

There are strategies available, he says, including “investing in natural capital to provide ecosystem services.”

Tree planting and better land use management can ameliorate some of the damages from a changing climate. But it would be better to invest in climate protection directly by reducing carbon emissions, according to Costanza.

He adds: “Climate damages and large scale class-action lawsuits, similar to those that were brought against the tobacco industry, are not out of the question.”

doi:10.1038/nmiddleeast.2017.25

Stay connected: