Using AI to control energy for indoor agriculture

30 September 2024

Published online 9 April 2018

Finger bone fossil reveals the complex human migrations out of Africa during a time when Saudi Arabia was wet grassland.

© Ian Cartwright

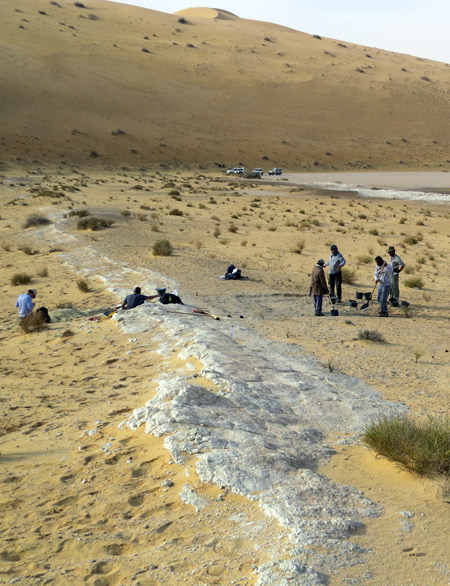

The multinational Palaeodeserts Project has spent years combing the deserts of Arabia for evidence of early human occupation and ancient environment. Its efforts paid off when a team, excavated the site of Al Wusta and unearthed a Homo sapiens finger bone at least 85,000 years old. The find is reported in a study published today in Nature Ecology & Evolution1.

The team was led by Michael Petraglia at the Max Plank Institute for Science of Human History, Jenna, who describes the discovery as “a dream come true” and says it was “like finding the needle in the haystack.”

“Traditionally, the movement of modern humans out of Africa, has been conceived of as a single rapid movement 60,000 years ago,” says Petraglia.

According to this theory, migrating groups would have moved along the coastlines, following the Levantine corridor alongside the eastern border of the Mediterranean basin, living off marine resources, and using stone tools as they moved across Eurasia.

“Now, we have a find that’s [at least] 85,000 years old which suggests that Homo sapiens have been moving out of Africa something on the order of 20 to 25,000 years earlier than supposed,” he says.

The discovery supports an argument that Petraglia and his team have been making for more than a decade: that there were multiple dispersals out of Africa, and that these spread further than previously known. It indicates that out-of-Africa migrations happened in continuous waves and trickles over a prolonged period and, possibly, through a different route that cuts through the heart of Saudi Arabia; the terrestrial heart of Eurasia.

The Nefud desert in northern Saudi Arabia is now an arid sand sea, but that was not always the case. Satellite images reveal a network of thousands of ancient streams and lakes that coursed through Arabia.

Petraglia and his team surveyed many of these lakebeds, one of which was the site of Al Wusta. “As soon as we got there we started to find stone tools and fossils. And that’s how it began,” he recalls.

The study shows that modern humans were in Asia prior to 60,000 years ago.

Huw Groucutt, archaeologist at the University of Oxford and lead author of the study, says that the team immediately discovered “outcrops of bright white sediments which are ancient lake deposits” that painted a vivid picture of the climate of the time.

As well, there were hundreds of animal fossils of species such as hippopotami, tiny fresh water snails and tools made by humans at the site. Hippos in particular live in muddy conditions, or on the shores of rivers and lakes.

“When humans were living there 90,000 years ago, it was not a desert,” says Groucutt. Monsoonal rains across the interior of Arabia had transformed the peninsula into a humid grassland area covered by lakes, crossed by rivers and with abundant animals.

Migrating humans “moved into Arabia during a time of improved climate,” aided by summer rainfall, explains Groucutt. Bands of hunters and gatherers lived around a small but permanent freshwater lake.

While surveying the site, Iyad Zalmout, a paleontologist of the Saudi Geological Survey (a partner in the excavations), found a 3.2cm-long finger bone fossil, and immediately suspected it was human, recounts Petraglia.

The fossil was sent around the world to different labs for CT scanning to create a 3D model.

© Michael Petraglia

The fossil itself was directly dated with a technique called uranium series dating––direct dating is a more reliable method than dating based on materials from the surrounding archaeological context, but it’s not always possible.

However, the team also dated sediment deposits around the site and tested the age of a hippopotamus tooth using electron spin resonance and optically stimulated luminescence techniques.

With three samples tested, using different techniques, and yielding roughly the same date, Petraglia became “very confident about the age of the site.”

The fossilized finger turned out to be the oldest remains of our early ancestors found outside of the Levant and Africa, becoming a new reference point for early human migration across Arabia.

“At the moment, many researchers think that there was a very small migration to the Levant about 100,000 years ago, but [that] this was a local movement just to the doorstep of Africa, and those people died out,” explains Groucutt.

Then, the theory suggests, there was a later singular migration around 60,000 years ago.

Recent modern human fossils from the Levant extend the date of human migration out of Africa to at least 177,000 years ago2. Finds further suggest the presence of modern humans 120,000 years ago in east Asia3, dismissing the first part of the theory and pushing back the date of human migration out of Africa.

There has been limited archaeological attention given to traces of early humans outside Europe, until recently. This meant that little fossil evidence of early humans was recovered in the lands between the Levant and eastern Eurasia, explains Petraglia.

The Al Wusta fossil, however, provides a crucial link between the Levant and eastern Asia, demonstrating the widespread geographical area of ancient migration and “adds to a growing number of studies that shows that modern humans were in Asia prior to 60,000 years ago,” says Christopher Bae, paleoanthropologist at University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa, who was not involved with this study.

Petraglia and Groucutt both emphasize that the human migration out of Africa was continual, expansive and occurred in multiple waves that corresponded with wet phases in the Arabian climate. “It’s not just an expansion and then a later re-migration out of Africa. What we’re showing is that the story is much more complicated,” Petraglia says.

Previously, the Arabian Peninsula has long been thought to be far from the main stage of human evolution. “This discovery firmly puts Arabia on the map as a key region for understanding our origins and expansion to the rest of the world,” he says.

doi:10.1038/nmiddleeast.2018.43

Stay connected: