Using AI to control energy for indoor agriculture

30 September 2024

Published online 8 July 2019

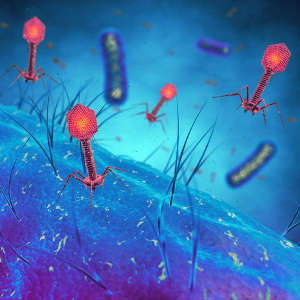

A recently discovered abundant virus has probably existed in the human gut for millions of years.

nobeastsofierce Science / Alamy Stock Photo

“This is the first time that a human-associated phage has been shown to have a truly worldwide distribution,” says lead author, and bioinformatics expert, Robert Edwards of San Diego State University. “It is remarkable that everywhere we find humans, we also find crAssphage.”

Through an enormous team effort, the study analyzed 32,273 DNA sequences of the gut virus from more than 60 countries. They found thousands of subtly different crAssphage strains around the world that tend to locally cluster within countries, which could be partially explained by recent patterns in human migration.

They also examined DNA from remote human populations and found crAssphage-like sequences in samples from Malawi and from the Amazonas of Venezuela.

“We were driven by curiosity,” says Ramy Aziz, a co-author at Cairo University, Egypt, who was among a few investigators in Africa. “The phage turned out to be much more deeply rooted in the human lineage than expected.”

Searching for crAssphage in our primate relatives

To investigate the phage’s evolutionary history, the team searched for crAssphage-like sequences in five species of non-human primates: baboons, gorillas, chimpanzees, howler monkeys and lemurs.

Initial tests using a DNA sequence comparison tool, called BLAST, did not yield significant hits for such sequences. But when Bas Dutilh, of Utrecht University, another corresponding author, collected those seemingly insignificant hits and used another data visualisation method called a dot plot, a clear similarity emerged. Considering that crAssphage had never before been found outside the human context, this was an astounding find.

The similarity is indicative of the long-term genomic stability of crAssphage in the primate gut, and suggests there is “a triumvirate evolution between the virus, its host (a bacterium), and humans and other primates,” says Edwards. “This evolutionary battle has been waged for millions of years.”

A benign, quiet resident

By analyzing genetic and human health data from more than 1,000 participants of the Dutch LifeLines DEEP cohort, the team found that crAssphage is not associated with differences in diet or any indicators of health or disease.

This begs the question of what role crAssphage might play. “Our research suggests that crAssphage is benign. It has been so successful and lasted so long by not causing any problems!” Edwards says. As it is not yet known whether crAssphage actively shapes or passively shadows its host, he intends to explore this topic in more detail.

“We also don’t fully understand the role of phages in the human microbiome,” he adds. “They could be altering the constituents of our intestines … and are certainly likely to affect how drugs work.”

Based on the evidence, Dutilh agrees that crAssphage “is indeed benign.” The findings open up many new questions. “It will be very interesting to determine its host range. Is it highly specific like many other phages, or can it infect different hosts? Could that be why it is so abundant?”

Future directions

The phage could be useful in forensic applications as a rapid and reliable marker for water contamination. “The local clustering we found in this study suggests a potential for using crAssphage for tracking the source of faecal samples,” says Aziz. “With current efforts to characterise differences between crAssphage variants around the globe, it might also be possible to use specific crAssphage sequences to track human migration.”

Work is also underway to uncover evidence of crAssphage in early humans. The team has so far examined DNA samples from Ötzi, the oldest known remains of a European man who lived between 3400 and 3100 BCE, and three pre-Columbian Andean mummies dating back at least to the 11th century AD. Although they have not yet found any hits, this may be due to the difficulty of finding intact DNA from ancient intestines. “We are in the process of setting up a special lab to analyse ancient DNA at Utrecht University, including extraction, sequencing, and bioinformatics analysis,” says Dutilh.

doi:10.1038/nmiddleeast.2019.96

Stay connected: