The Missing Kingdom: Why Fungi Must Be Central to Conservation Strategy

28 December 2025

Published online 9 January 2020

Despite overall declines in child growth failure, nutrition inequalities persist across low- and middle-income countries at the local and regional levels.

Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, University of Washington, USA

“This is another wake-up call that the current approach is not working where stunting and wasting are the worst, like in parts of Niger and Chad,” says Kevin Phelan, nutrition advisor at the Alliance for International Medical Action in Paris, who was not involved in the study. “We need new strategies based on earlier diagnosis, simplified treatment, and improved access to nutritious diets for young children, including direct food supplementation, which has been shown to improve growth and reduce wasting.”

Child growth failure is manifested in the form of stunting, wasting and lower than average body weight in children under five. It is associated with brain and developmental disorders that have impacts on school and work performance, as well as increased risks for infectious disease and reproductive health later in life. Stunting, measured as low height-for-age, is the most widespread form of chronic malnutrition globally.

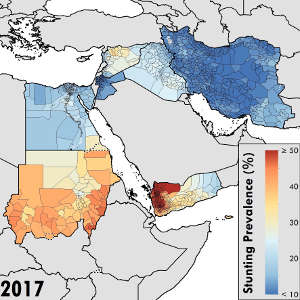

The study mapped estimates of child growth failure indicators across 105 low- and middle-income countries at a resolution of 5x5 square kilometres, covering the period from 2000 to 2017. It provides a means to highlight communities most in need of support.

“Due to the overlap of stunting with other socioeconomic and environmental factors, precision mapping helps identify communities likely experiencing multi-dimensional disadvantage,” says corresponding author Simon Hay, director of geospatial science at the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) at the University of Washington, USA. By determining where vulnerable populations reside, he explains, the maps can help policymakers plan locally tailored interventions and direct resources in a more targeted manner.

Across the Middle East, overall prevalence of stunting decreased from 30.5% to 22.4%, representing 10 million children in 2000 and 9.2 million affected in 2017. Countries in the region with the highest prevalence of stunting by 2017 were Yemen (45.2%) and Sudan (37.6%).

“Progress in reducing the rates was evident across the region, particularly in Iran, Egypt and Iraq,” says Hay. “However, even with the overall reduction of the national prevalence, wide within-country disparities were apparent.” In Yemen, for example, in 2017, stunting levels ranged from 18.4% in Al Ghaydah district in Al Mahrah governorate, to 61% in Shaharah district in Amran governorate. Stunting levels in Sudan ranged from 26.2% in Khartoum Bahri district in Khartoum state to 47.7% in Geissan district in Blue Nile state; and in Iraq they ranged from 12.6% in Penjwin district in As-Sulaymaniyah region to 27% in An Nasiriyah district in Dhi-Qar region.

As with their previous study2 mapping child growth failure in Africa between 2000 and 2015, the researchers have made their interactive maps publicly available from the Global Health Data Exchange via a user-friendly data visualisation tool.

The findings are pertinent to assessing how realistic it is for countries to meet the World Health Organization’s Global Nutrition Targets for 2025. The projected outlook suggests just over a quarter of all low- and middle-income countries will achieve national-level targets for stunting and wasting, and fewer than five percent are likely to achieve both targets at the subnational level.

Of the eight countries analysed in the Middle East region (Iran, Iraq, Jordan, Palestine, Syria, Yemen, Egypt and Sudan), five are estimated to be on course to meet the targets for stunting at the national level. “At finer scales, only Iran, Jordan and Palestine are likely to meet the stunting target in all of their first (e.g. provinces) and second (e.g. districts) administrative subdivisions in 2025,” the researchers say.

doi:10.1038/nmiddleeast.2020.2

Stay connected: