Using AI to control energy for indoor agriculture

30 September 2024

Published online 11 May 2020

COVID-19 has put the illegal wildlife trade under the spotlight by highlighting the threat posed to human health.

ROUTES

The dangers of the legal and illegal wildlife trade are returning to public attention in light of the COVID-19 pandemic, raising questions in the Arab region, among others, about how to deal with it and with wildlife markets, according to Elsayed Mohamed, Middle East and North Africa regional director of the International Fund for Animal Welfare. “There is strong evidence that something is wrong and that we need to reconsider the wildlife trade,” he says.

This has become especially apparent as a new report highlights the Middle East as one of the world’s most prominent transit hubs for wildlife trafficking by air. The report1 , “Runway to Extinction: Wildlife Trafficking in the Air Transport Sector”, examined the trends, transit routes and air trafficking methods used by wildlife smugglers to exploit the aviation industry between 2016 and 2018.

The report’s author, Mary Utermohlen, a wildlife crime specialist with the Center for Advanced Defense Studies, says Middle East airports are used as transit points between source and demand countries in Africa, Asia and Europe.

There is particular concern about the potential of exotic live animals to spread disease in the Middle East, says Utermohlen. “Birds, reptiles and primates carry diseases that can be transmitted to humans, and species like falcons, Nile crocodiles, baboons and certain monkeys are in demand to varying extents in different Middle Eastern countries.”

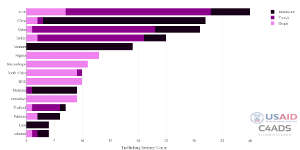

According to the report, trafficking instances in the Middle East nearly always flew into Dubai, Doha, or Istanbul, and most continued on to Asian destinations. To a lesser extent, airports in Egypt, Lebanon and Iraq were also used as transit points by wildlife traffickers.

“One of the more interesting trends we noticed was the concentration of trafficking attempts for certain products in certain Middle Eastern airports,” says, Utermohlen. Traffickers moving pangolin products tended to favour flight routes passing through Turkey. Rhino horns often moved through Qatar, and ivory usually passed through the United Arab Emirates. “This is probably a result of the different flight routes available to traffickers leaving certain African countries for specific Asian destinations,” she explains.

ROUTES

Enlarge image

“People who come into contact with wildlife, especially for prolonged periods, have a higher risk of contracting zoonotic infections,” says Amira Roess, professor of global health and epidemiology at George Mason University in the USA.

The U.S. Centre for Disease control estimates three out of every four new or emerging infectious diseases in people come from animals. Tackling wildlife trafficking is regarded as one of the keys to preventing future pandemics that originate from zoonotic diseases.

Roess, who currently oversees several longitudinal studies to understand the emergence and transmission of zoonotic infectious diseases globally, says that, like much of the world, the Middle East does not have animal or wildlife surveillance systems to detect when zoonotic outbreaks occur.

Live animals and meat likely present the greatest risk of disease transmission “as pathogens are transferred through contact with bodily fluids, excretions or by direct consumption,” according to global wildlife trade monitoring network TRAFFIC.2

‘Runway to Extinction’ notes that knowing the trafficking patterns, such as which animal or wildlife product is flown through which airport, can help airport authorities target the transport methods most commonly used by traffickers.

Utermohlen says Middle Eastern countries should work on counteracting wildlife trafficking activities in the air transport sector by working on awareness, training, enforcement, policy development, and detection, and by increasing penalties to reduce domestic demand for exotic wild animals.

doi:10.1038/nmiddleeast.2020.55

Stay connected: