Using AI to control energy for indoor agriculture

30 September 2024

Published online 7 September 2014

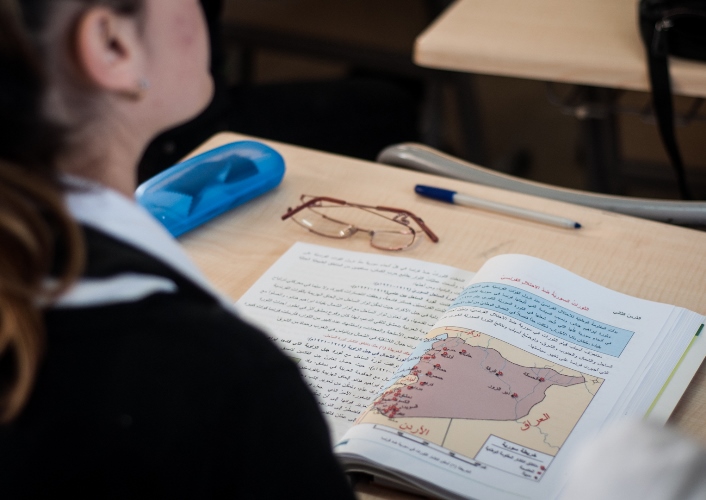

Schools in Iraq continue to struggle, limiting learning opportunities for the country’s youth. Educational indicators show a marked decline as wars, sanctions and sectarian strife have stripped Iraq’s education system of resources.

That goal has been put on hold by the latest wave of conflict to hit Iraq. Along with her family, Maryam is now seeking shelter with her family in a hot, crowded tent in the courtyard of Mar Yousef Church in Erbil, capital of the Kurdish region of Iraq. Along with more than one million displaced children in Iraq, Maryam will not be returning to the classroom this year.

The recent displacements in Iraq due to the seizures by militants of the Islamic State has sparked an emergency that forced the transformation of 2,000 schools into makeshift camps for displaced families. More than half of Iraq’s 95,666 teachers have been affected, and final examinations from the previous school year have been postponed again because of insecurity.

Violence has long been a challenge to a government struggling to rebuild its education system. Iraq has the second youngest population in the Middle East and North Africa region; an inability to educate its children will carry a heavy future cost.

Before the 1990s, Iraq boasted that it had the best education system in the Middle East, statistics showed it led the way in educational access, literacy and gender equality. The state provided free education to students from primary to university levels.

Then the Gulf War and the debilitating economic sanctions that followed started the education system’s decline. The loss of oil revenues which supported public schools and universities caused a massive shortage of learning resources. Teachers’ salaries dropped to US$6 per month and many school facilities were destroyed by bombings targeting civilian infrastructure.

The 2003 US led invasion and ensuing years of war further worsened the situation as the education system was crippled by insecurity, inadequate facilities and a shortage of qualified teachers.

In Baghdad, classrooms built to accommodate 25 to 30 children now hold more than 80, and sometimes up to 120 students.

Today, educational opportunities in Iraq are still hampered by the deteriorating security situation, internal displacement, inadequate facilities and poverty.

Furthermore, the outdated curricula do not meet the needs of students, says Bie Kentane of the Brussels Tribunal in a 2013 special report for the UN. A shortage of qualified educators and inefficient management is further jeopardizing the education of children.

The most recent UNICEF figures on primary school enrolment show more boys (93%) are enrolled than girls (87%), with the overall total falling far short of Iraq’s 2015 Millennium Development Goal target of 98%. Fewer than half of children who enroll in primary education actually finish school.

With each successive year, fewer children continue their education. Just under half of secondary school age children go to secondary school. Of those not attending, one in seven are still attending primary school while the remainder are out of school altogether.

In 2012, then education minister Mohammed Tamim said Iraq needed 12,000 new schools and 600 more each subsequent year. As of 2012, only 2,600 had been built.

In Baghdad, classrooms built to accommodate 25 to 30 children now hold more than 80, and sometimes up to 120 students. Save The Children (STC) reports that the shortage of schools has resulted in two to four shifts being run daily out of the buildings that are still used. Overcrowding and shorter days have significantly reduced teacher-student contact time.

UNICEF and STC say schools suffer a severe lack of basic resources and teaching aids such as desks, chairs, books and blackboards. Schools are frequently without clean water supplies, sanitation and garbage disposal systems. The unsanitary conditions put children at greater risk of infections and illness and the poor learning environment negatively affects their outlook.

Studies by numerous NGOs have found that girls are more likely to stop attending school if there are no proper sanitation facilities. Progressive reforms in the 1970’s had given girls in Iraq equal access to education. But today, girls are again suffering a disadvantage compared with boys their age.

Kentane reports that girls account for 44.7% of students at the primary level, but most will not go on to intermediate and secondary education as 75% drop out during or after primary school.

An extensive study by UNICEF on girls’ education in Iraq published in 2010 reported no significant improvement in girls’ enrolment in compulsory primary education, and that the rates of girls’ enrolment declined sharply with each successive grade. While no follow-up study has been conducted, UNICEF education advisors say increased violence in general means fewer girls in schools, because the insecurity often restricts girls’ movements.

But it’s not just security, UNICEF adds; the reasons girls drop out are more complex and far-reaching.

Financial difficulties may mean girls face pressure to help support or care for their families. In some cases, girls do not attend school because of the wishes of their parents.

In rural areas, girls are more likely to stop attending school earlier and arranged teenage marriage is still practiced. In both urban and rural areas, girls are also less likely to attend school if it is far from their home.

A landmark report published in February 2014 by the Global Coalition to Prevent Education from Attack (GCPEA) revealed that the targeting of schools is a much larger problem than previously documented.

Schools that should be safe havens of learning are damaged or destroyed during attacks or fighting, or overtaken and used for military purposes – a direct contravention of The Hague IV Conventions on Laws and Customs of War on Land, says Kentane.

Militias and security forces sometimes intentionally target schools. With their children’s safety paramount, more parents opt to keep them at home. Teachers, who are also targeted, continue to quit through fear.

Baker, of Child Victims of War, says that Islamic State is also “recruiting children and youth from the poorest communities with little education and who have no hope for the future.”

The failure of the system to educate children properly means their opportunities later in life are reduced, Kentane says. Both the community and the state will suffer as the implications of an uneducated society are further woven into the fabric of Iraqi society.

doi:10.1038/nmiddleeast.2014.218

Stay connected: