Using AI to control energy for indoor agriculture

30 September 2024

Published online 21 August 2015

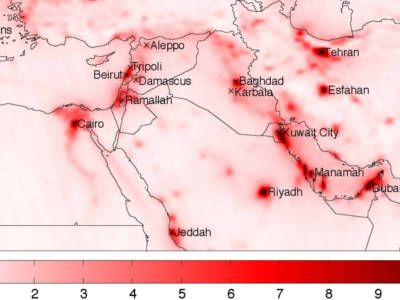

Conflict, economic recession and favourable policies in a few countries have surprisingly reduced air pollution in the Middle East since 2010.

© Lelieveld et al. Sci. Adv. 2015;1:e1500498

The findings are part of a new study led by Jos Lelieveld of the Max Planck Institute for Chemistry in Mainz, Germany, published today in Science Advances.

Lelieveld and his colleagues ‑ including scientists from King Saud University (KSU) and King Abdullah University for Science and Technology (KAUST) – have been using satellite platforms to observe the emissions of nitrogen oxides in the Middle East for 10 years.

Their results are the first to reveal a correlation between the political climate and the atmospheric one in the Middle East. The study is the first to employ both stationary and orbiting satellites to produce a 10-year dataset in high resolution.

“In the Middle East, large changes of NO2 have occurred,” Lelieveld told a press conference on Thursday, describing the atmospheric changes as “unique worldwide.”

“These [findings] disagree with scenarios used in prediction of air pollution and climate change for the future,” he added.

In the past, projections were almost always linked to levels of CO2 in the air – which Lelieveld says is not a valid predictor of climate trends in the Middle East. He tracked NO2, a byproduct of fossil fuel use and road traffic exhaust and a highly reactive gas that contributes to reactions producing ground-level ozone (smog), and one which poses the greatest hazards to health.

The Middle East has no air-quality networks on the ground, therefore long-term space observatories of NO2 were used to study air pollution emissions in the region.

It is amazing how strong the changes have been in the Middle East.

Lelieveld found that from 2005 to 2010, the Middle East recorded the world’s fastest-rising air pollution emissions. A similar trend was plotted in East Asia, and has been linked to economic growth there. “However, [the Middle East] is the only region where this pollution trajectory was interrupted around 2010 and followed by a strong decline.”

The team attributes the decrease to some good practices, mainly implementation of environmental control measures. But, curtailed industrial activity caused by economic pressure and conflict is the primary reason for the changes in the Middle East’s environmental trends.

“In Syria and Egypt, armed uprisings and political crises have led to economic and social pressures. In Syria and Iraq, the [outpouring] of refugees has reduced pollution.” No environmental policies were implemented in these countries after 2010, yet there was a decline in NO2 emissions by 20-50%.

“It is amazing how strong the changes have been in the Middle East,” says Lelievand. He explains that unlike other crisis areas, the trends in this region changed sharply rather than gradually.

He cited how the activities of the insurgent group Islamic State (IS) are rapidly changing trends. When people flee en masse from one part of Iraq to another, the atmospheric trends change. Pollution decreases in the area from which they leave and increases wherever they find refuge. This correlates with information from the UN on the movement of these refugees.

Apart from the countries in which good practices are responsible for cleaner air, specifically the Gulf states, this information is purely diagnostic.

For war-affected countries, Lelievand concedes that air pollution information is not going to greatly alleviate their problems. But, this information and new diagnostics may at some point be analysed for each country and used be policymakers in the region, he adds.

“I don’t want to create the illusion that air pollution measurements [taken] from space will help people in areas like Iraq and Syria. It’s a simple diagnostic of what is going on, which is possibly helpful because in many cases when policies are implemented and emissions are estimated, you can improve emissions [based on these numbers].”

The researcher says he will continue his observations of the region, hoping that in the future he will have access to more advanced ecological satellite imaging instruments that will provide a wider array of information, in high resolution and across different timeframes. He says he’s collaborating with scientists at KAUST, Saudi ARAMCO, and in Egypt and Lebanon to that end.

“What’s happening in the Middle East is unusual,” says Lelievand. “I am hoping that the world is being reminded again that we need the international community to get active and try to help resolve some of these problems.”

doi:10.1038/nmiddleeast.2015.143

Lelievand, J. et al. Abrupt recent trend changes in atmospheric nitrogen dioxide over the Middle East. Sci. Adv. http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.1500498 (2015)

Stay connected: