Using AI to control energy for indoor agriculture

30 September 2024

Published online 25 October 2016

Researchers are working to overcome the paucity of Middle Eastern genomics data.

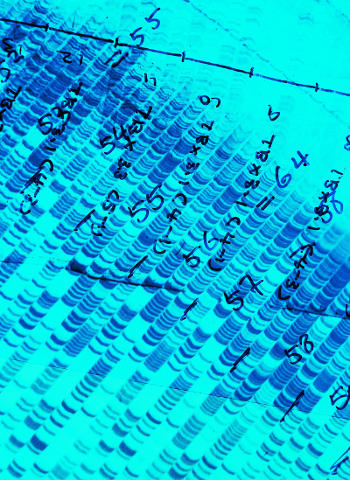

© PunchStock/Digital Vision

As the genomics era dawns, scientists have identified a wide range of minor variations in the human genome that are associated with susceptibility to certain diseases or conditions. The variations may not cause the conditions, but are inherited along with them and serve as reliable markers. However, since Middle Eastern diversity is poorly captured in existing genomic data, these markers become unreliable in the region.

An analogy for the problem is looking up information in a book using a page number reference from a different edition ‑‑ the book has the same contents, but the guideposts become misleading.

The emerging field of precision medicine uses these markers to customize healthcare by predicting how an individual will respond to a drug or therapy based on their genome, underlining the need to capture the genetic diversity of the Middle East.

“Integrating genomics with medicine is going to be a hot topic for the next decade,” says Khalid Fakhro of Sidra Medical and Research Center and Weill Cornell Medical College-Qatar (WCM-Q). “Without sufficient diversity [in genomics data], there’s no way of achieving the vision of personalized medicine in under-represented parts of the world.”

A recent WCM-Q study of type 2 diabetes in Qataris demonstrated the potential pitfalls of the lack of diversity in genomics data. “We looked at over 60 markers in more than 1000 individuals but only replicated two European loci related to type 2 diabetes,” says Fakhro.

In other words, the major genetic factors linked with type 2 diabetes in Middle Eastern populations probably aren’t the same as those in European and Asian populations. These factors will remain unknown without further data from larger cohorts, limiting the advancement of personalized medicine in these countries, which have among the highest rates of diabetes in the world, with three Arabian Peninsula countries in the global top ten.

Genome projects underway in Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and Egypt are a first step towards addressing the problem. “We’re planning to build an Egyptian reference database and then use it to micro-dissect Egyptian cancers,” explains Adel-Rahman Zekri of the National Cancer Institute at Cairo University, who is leading the Egyptian genome project.

Work by Zekri and others has shown that the genetic basis of several cancers differs between European and Egyptian populations.

“These studies have shown that there is a difference between the Egyptian population and the European population,” says Zekri. “In the new era of targeted molecular therapy and personalized medicine, I think every Arab country needs to build a genome database and to communicate and collaborate on this project.”

Contributing DNA for research could be considered a form of charity, one of remarkable benefit to society.

Public awareness also needs to catch up to the new technologies.

Personal genomics companies in Europe and the United States generate large amounts of data, and individuals can choose to share their sequence data by depositing them in public databases. High-profile projects sequencing famous people such as the renowned scientist, Steven Pinker, have raised awareness of the benefits and risks of sharing sequence data; likewise, Angelina Jolie generated significant debate about informed healthcare decisions and genetic tests by announcing that she had undergone a double mastectomy after a BRCA test showed she had a high risk of developing breast cancer.

So far, genomics hasn’t reached similar levels of visibility in the Arab world. Understanding and awareness of genomics – particularly personal genomics – remain relatively poor in the region.

“There is this widespread philanthropic attitude in the Arab world that could be tapped into, but no one has conveyed to the public that contributing their DNA for research could be considered a form of charity, one of remarkable benefit to society. This is something that would resonate very well in our countries,” says Fakhro, who contributes to Qatar’s genome project.

“It’s one thing to give a saliva or blood sample and help research without compromising your own identity since it’s all anonymized and aggregated, but it would extremely powerful if individuals decide to continue sharing their health data over the course of their life," he says.

The enthusiasm generated by greater public awareness and discussions of genomics might also encourage investors and startups to focus on personal genomics, and the resulting growth in the private sector could help supplement national projects.

As the public and private infrastructure for genomics research continues to develop in the region, the need grows for an active regional genome centres to help curate the data and foster collaboration. Likewise, a legal framework regulating access to personal data and genetic testing needs to be established. The national genome projects have begun the process of uncovering Middle Eastern diversity, but a robust framework is needed to help manage and share the resulting data.

Increasing the diversity in global genomics data sets doesn’t only benefit underrepresented populations. By providing a richer picture of human variability, this data helps researchers properly interpret the relevance of the variants identified in European populations.Variants that are rare and difficult to detect in Europe but common elsewhere may be linked to particular traits or diseases.

Putting together the genetic puzzle that comprises humanity can only happen, the scientists say, if the world casts its view broadly enough to see all the pieces.

doi:10.1038/nmiddleeast.2016.193

Stay connected: