Using AI to control energy for indoor agriculture

30 September 2024

Published online 7 June 2017

The 300,000-year-old skull segments carry insights into the origins of our species and connect Morocco with complex evolutionary changes taking place across Africa.

© Philipp Gunz, MPI EVA Leipzig

The cave known as Jebel Irhoud, a site originally blown open by mining in the 1960s, is where scientists have uncovered the fossilised remains of five people, their stone tools and the bones of the animals they hunted. Advanced analysis suggests they are 300,000 years old.

“This material represents the very root of our species –– the oldest Homo sapiens ever found in Africa or elsewhere,” says paleoanthropologist Jean-Jacques Hublin of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology who led the research team.

These earlier humans had sharp flint spears, which they used to hunt, butcher and consume game, including gazelle, zebra and wildebeest. They knew how to make fire. The landscape around them – grasslands dotted with clumps of trees – was the western part of a wetter, greener hinterland that was home to leopards and lions, and which stretched across what is now the Sahara desert all the way to the Sahel.

The discovery, published in two Nature papers today, has major implications for our understanding of the evolution of our species.

“We used to think that there was a cradle of mankind 200,000 years ago in east Africa. Our new data reveal that Homo sapiens spread across the entire African continent around 300,000 years ago,” says Hublin, “Long before the out-of-Africa dispersal of Homo sapiens, there was dispersal within Africa.”

© Sarah Freidline, MPI-EVA, Leipzig

Subsequent analysis was complicated by persistent uncertainties.

The new excavation, co-directed by Hublin and the Moroccan paleoanthropologist Abdelouahed Ben-Ncer of L'Institut National des Sciences de l'Archéologie et du Patrimoine (INSAP) in Rabat, produced what the scientists termed ‘wow’ results.

“Well-dated sites of this age are rare in Africa. We were fortunate that many of the Jebel Irhoud flint artefacts were heated in the past,” says Daniel Richter an expert in geochronology at Freiberg Instruments in Germany and part of the Max Planck team. Richter used state-of-the-art thermo-luminescence dating methods to establish a consistent chronology for the new hominin fossils and the layers above them.

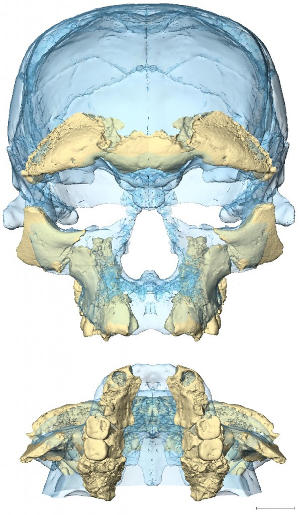

The treasure trove includes a partial skull, a well-preserved face, an adult jaw-bone complete with a full set of teeth and other post cranial remains.

They are thought to represent at least five individuals: three adults, one adolescent, and one 8-year-old child.

Comparing these with the heads of ancient humans, Neanderthals and more modern fossils reveals a surprising combination of modern and archaic features. The Irhoud people had modern faces – short, flat and retracted under the cranium – but elongated lower brain cases on the back of the head that are more primitive.

This, Hublin suggests, indicates that different parts of the anatomy evolved at different rates, with facial features being fixed in the modern way early on and brain shape and possibly brain function taking a longer time to reach the modern condition.

“The story of our species in the past 300,000 years is mostly the evolution of our brains,” he says.

“North Africa has long been neglected in the debates surrounding the origin of our species,” says Abdelouahed Ben-Ncer. “The spectacular discoveries from Jebel Irhoud demonstrate the tight connections of the Maghreb with the rest of the African continent at the time of Homo sapiens’ emergence.”

© Jean-Jacques Hublin, MPI-EVA, Leipzig

Until recently the oldest confirmed human fossil came from Omo Kibish, Eithopia, at around 190,000 years old.

Taken together, the Homo sapiens fossils at the north, east and south of the continent indicate a more complex pan-African evolutionary history of our species than the cradle of humankind theory suggests.

“This [discovery] is an important contribution to understanding modern human origins,” Robert Foley, Director of Cambridge University’s Leverhulme Centre for Evolutionary Studies, who was not involved in the research, says.

“We have to think of Africa at this time as a mosaic of hominin populations, a network of gene flow and isolation, from which, in the end, tens of thousands of years later, one form becomes predominant. Unravelling how that happened remains a big challenge.”

doi:10.1038/nmiddleeast.2017.102

Stay connected: